Ever discovered a “fact” in your family tree that turned out to be completely wrong?

Most family trees are littered with them. Incorrect dates. Wrong parents. Entire branches connected to the wrong families.

The genealogy world recognized this problem years ago.

Their solution: the Genealogical Proof Standard—a framework designed to help researchers avoid building conclusions on shaky ground. It’s the difference between family stories and documented proof.

The Board for Certification of Genealogists developed these guidelines to maintain credibility in genealogical research. Follow them, and your conclusions carry weight instead of uncertainty.

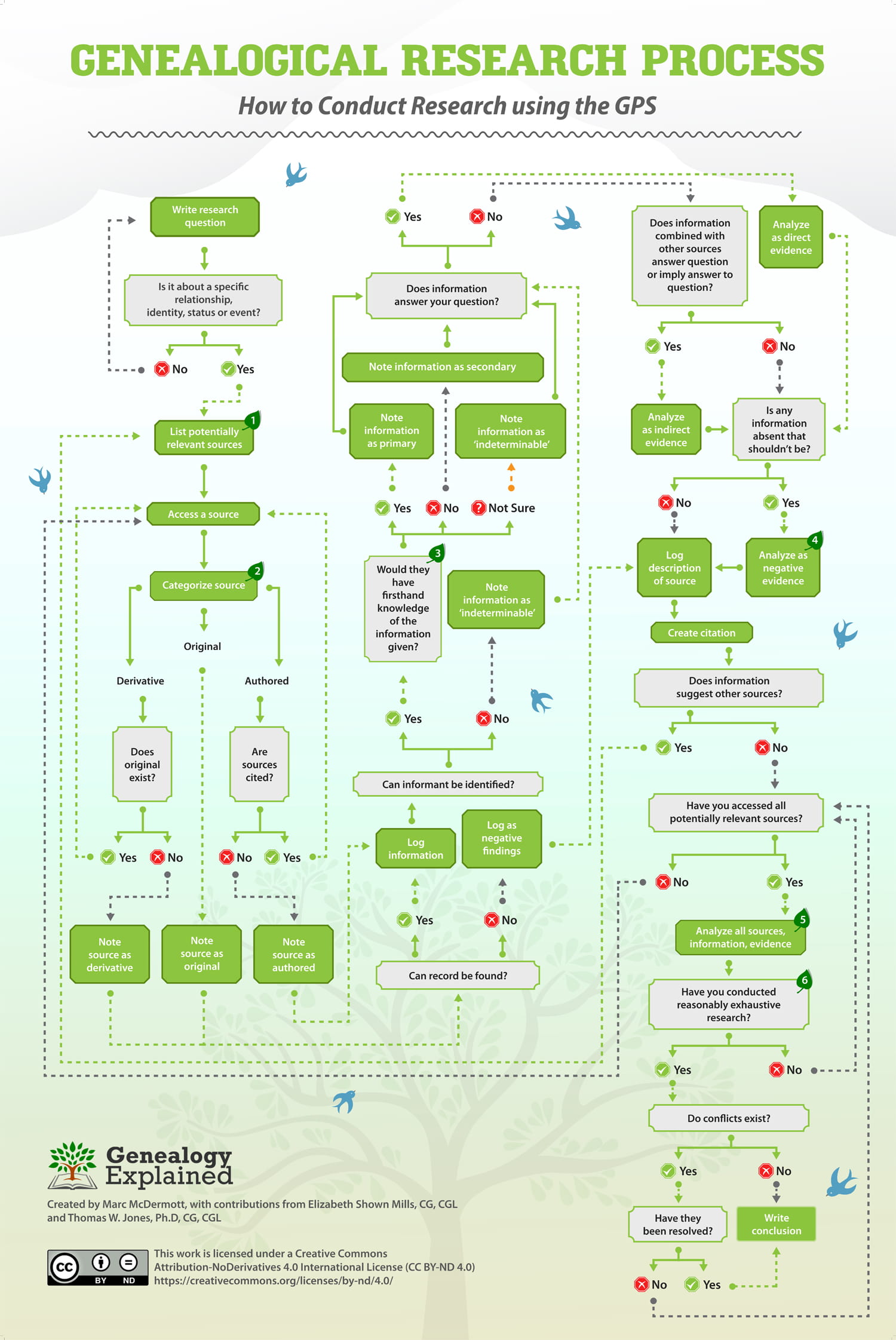

I’ve created a flowchart that breaks down the entire GPS process into actionable steps.

No jargon. No confusion. Just a clear roadmap to research that stands up to scrutiny.

References made in the graphic:

- List potentially relevant sources

- Categorize source

- Would they have firsthand knowledge of the information given?

- Analyze as negative evidence

- Analyze all sources, information, evidence

- Have you conducted reasonably exhaustive research?

Proof in Genealogy

“I just found out that I’m descended from King Edward V of England!” your friend tells you excitedly.

“Really?” you ask. “What proof do you have?”

How do we prove something when it comes to genealogy and family history research? Just how much information and evidence do we need?

The answer is, it depends.

You might only need one original record containing primary information from a trustworthy informant that provides direct evidence for your research question.

Or, it could take many derivative records containing secondary or indeterminable information.

Basic Terms to Know

When doing any work in genealogy, it’s important to know and understand the differences between sources, records, information, and evidence.

Let’s take a look at each in more detail.

Sources

The word source is often confused with ‘record’ in genealogy. Put simply, a source is a collection/container of records.

Some examples of a source are church registers, databases, authored genealogies, land deed books, vital record indexes and censuses.

A source should also not be confused with a repository. A repository is a physical location where sources are held (for example the New Jersey State Archives).

2There are three types of sources:

- Original: the original form of the record created at the actual time of the event–or not long after.

- Derivative: the copied, aggregated, or derivative version of original records. Derivative sources are usually created well after the actual event. For example, an index of vital records. Note that a ‘copy’ does not refer to a photocopy of an original record.

- Authored works: the published research already conducted on the person/family/area of interest.

As responsible genealogists, we want to seek out original sources when possible.

Derivative sources and authored works are fantastic finding aids to locate original records.

1When we set out to answer a new research question, we make a list of all potentially relevant sources that might provide information to help answer our question.

It’s critical that our list of potentially relevant sources also include sources that are likely to contain information which could contradict other information or disprove answers to our question.

If you’re not already familiar with the location, time period, subject, etc. that you’re researching, this step will take some time.

Records

Records are the individual page, line item, certificate, etc. within a source that documents an event or action.

Think of a death certificate. The source would be the actual collection of death certificates held at the particular repository, whereas the record would be the actual certificate of the person of interest.

Looking at the death certificate, there is a lot of information from various informants.

Information

The information provided in our example death certificate is what’s actually written on the paper–not what may be inferred or what our opinions are.

3Of course, not all information is the same. There are actually three distinct types of information:

- Primary: information/facts given by someone who was actually at the event. For example, the cause of death given by the medical examiner would be primary information.

- Secondary: information given by someone who was NOT physically at the event. This is information they may have heard or read elsewhere– it is hearsay. For example, the birth date of the deceased given by a spouse. Their spouse was not physically at the birth.

- Indeterminable: information given where the informant or how the informant knows the information cannot be determined.

Remember that the classification of information does not refer to the record as a whole, rather the individual pieces of information written on the record (death date, birth date, parents names, the cause of death, burial information, etc.)

Now that we have an idea of the different types of information found in records, let’s look at how to evaluate the information by the evidence it provides.

Evidence

Evidence is our interpretation of the information contained in a record. It’s how we think about and use the information to help answer our research questions.

It is intangible and exists only in our minds. There are three types of evidence:

- Direct: evidence that directly answers our question. For example, the cause of death listed on a death certificate.

- Indirect: evidence that suggests an answer to our question, but does not directly answer it. More than one piece of indirect evidence will be needed to answer our question.

- 4Negative: evidence that does not exist where we assumed it would. This leads us to make assumptions about the missing information. For example, you might infer that a child missing from a census record of his/her family has died prior to the census year. Negative evidence should not be confused with negative findings.

Evidence is ultimately what we are after to solve or prove our research question.

The Genealogical Proof Standard

Now that you have a better understanding of some basic terms, let’s dive into the GPS.

Just how much evidence do you need? And how should it be organized? What is best practice?

The GPS, was created to answer exactly those questions.

Because every case is unique, we can’t establish a specific number and say, “You must have five indirect pieces of evidence.” In some cases, five isn’t enough. In others, it may only take two.

Instead, the GPS sets standards that help you decide if you have enough evidence.

The GPS has five elements:

- Reasonably exhaustive research

- Complete and accurate citation of sources

- Correlation and analysis of the evidence

- Resolution of contradictory evidence

- A conclusion that is soundly reasoned and written coherently

Reasonably Exhaustive Research

6 At times, many of us find research exhausting. But that doesn’t mean we’ve done exhaustive research.

When it comes to GPS, this means that you’ve considered as many sources of potentially relevant information as possible within reason. You didn’t stop with just two or three bits of information and say good enough. You kept digging.

This includes seeking out sources that are likely to contradict any preconceived conclusion you may have. Don’t just seek out the sources you know are likely to agree with your hypothesis.

There are dozens of possible sources to be located. Some are original sources with primary information that offer direct evidence, and if you do manage to find them, wonderful.

But if all you find are bits of indirect evidence, you need to look for every source you can get your hands on: probate and court records, census listings, newspaper articles, church records, local histories, etc.

Each one adds a piece to the puzzle.

So how do I know when my research has met the standard of ‘reasonably exhaustive’?

The very first step is to know what sources are available for the time and place you’re researching.

If you’re not already familiar with what’s available and where to find it, I highly recommend purchasing the National Genealogical Societies’ research guide to whatever State you’re researching which you can find here: https://www.ngsgenealogy.org/ris/

Even when you know what sources are available, you won’t know you’ve been reasonably exhaustive until you’ve done the research – it’s impossible.

You can plan all you’d like, but that initial batch of sources you plan to analyze should and will suggest other sources.

Even once you’ve analyzed every source, I like to ask myself if I have enough evidence to make a conclusion that I feel confident won’t be overturned in the future if a new, contradictory source comes to light.

If I don’t feel confident, then I must seek out new sources until I am confident.

Understanding DNA evidence will be crucial when dealing with complex genealogical questions, and is a great source of new information as more people are tested.

But you shouldn’t rely on other people doing a DNA test when gathering evidence. Rather you should establish a plan of attack based on the question you’re trying to answer.

Seeking out targeted test takers based on their potential to answer your question is crucial in this stage of the GPS.

That’s reasonably exhaustive research – and yes it can be exhausting.

For more on researching your ancestors in the United States, I highly recommend Val Greenwood’s book, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy.

Complete and Accurate Citation of Sources

When you do locate a source, record where you found it as completely and accurately as possible.

This not only lets other researchers validate your information, but it makes it far easier for you to find the source again if you need to take another look.

Don’t wait to document your sources. Write them down as you find them, and keep track of them in a single, centralized location.

A proper source citation generally includes the name of the author, title of the source, a catalog or other identification number, publication date, page number, and date and place you accessed the source.

Also, be sure to write down in which library, courthouse, archive, or other location you found it.

And above all, ALWAYS make a copy of the title and/or section pages if your source has one.

What may seem at first to be an original source of church marriage records might actually be a handwritten copy done years after the original which would make that source a derivative and thus less credible.

I once spent days trying to resolve contradictory information in a church marriage register book. The marriage event took place in 1886, so I just assumed what I was looking at was written at that time.

Only after pulling out my hair for days trying to resolve the issue did I think to go back to the title page of the book to realize it was not an original. It was a copy made in 1924 – 38 years after the event!

So always make sure you understand and cite exactly what you’re looking at.

For more on citations, I highly recommend reading Evidence Explained by Elizabeth Shown Mills.

Correlation and Analysis of the Evidence

Just gathering evidence isn’t enough.

5You have to decide if your sources and information are reliable and useful, and then you must build a case.

Not every source is reliable/credible.

Just because you found it online or someone else said it was so, does not make it true.

That’s called hearsay.

More often than not, user-created family trees on sites like Ancestry are littered with incorrect names, relationships, dates and any number of other facts.

Don’t just copy what you see in someone else’s tree unless they have a documented trail of evidence.

If you have five different pieces of information that imply five different years of birth for the person you’re researching, obviously at least four of them are wrong.

Careful analysis of each piece of information and source is required to decide which is most likely to be accurate.

Correlating sources means taking information from two or more sources and combining them to generate new knowledge.

For example, say you don’t have a birth certificate for Michael Fleming, but you do for his brother Stephen.

In another source, Stephen states that Michael is exactly three years and seventeen days younger than him.

By correlating these two sources, you have some good indirect evidence to possibly prove Michael’s date of birth.

Just remember you still need to perform reasonably exhaustive research and that the more indirect evidence you use (instead of direct), the more evidence is required to reach your conclusion.

Resolution of Contradictory Evidence

What happens when you have sources and information that contradict each other? When using the GPS, you can’t just ignore one and pick the other willy-nilly.

Just because you see something you don’t think is true about your ancestor, doesn’t mean you can ignore it.

Careful analysis is required. All conflicts must be resolved before you can prove your case.

That’s not to say that every conflict can or will be resolved. Some may never be and you won’t be able to prove your conclusion without additional evidence.

A large part of resolving a conflict is determining how or why a particular piece of information is wrong.

Often this means digging up additional information. But once you can demonstrate that the contradictory information is not correct, you have resolved the conflict.

Contradictions can be annoying. They force us to dig deeper and reason more carefully. But that is exactly what we should be doing anyway.

If you cannot explain away the contradictory evidence, it will be impossible to build a convincing proof.

For more on analysis and conflict resolution, I highly recommend Mastering Genealogical Proof by Thomas Jones.

Conclusion Soundly Reasoned and Written Coherently

For some genealogists, writing a soundly reasoned and coherent conclusion is the hardest step. But it is also one of the most important and useful things that we can do.

When building a proof using GPS, you assemble and link together all of the evidence that you found. You build a case that is sound and logical that leaves no conflict unresolved.

Then you put it in writing.

If you can’t write a coherent, soundly reasoned conclusion, chances are you still have more research to do first.

If that’s the case, repeat step one of the GPS. Remember, not all research questions can be answered.

Once you’ve written your conclusion, measure its completeness and credibility against the GPS. If all standards are met, you have proved your research question!

Who Should Use the GPS?

The short answer is everyone.

Professional genealogists rely on the GPS to ensure the work they do for their clients is of the highest quality.

Anyone submitting a case study to a genealogical journal or magazine is certainly going to be expected to follow the GPS.

But the more you use it in your everyday research, the better off you are going to be.

Don’t wait until you’re ready to start preparing a written genealogy or family history. Use the GPS every step of the way.

It will help guide your research and ensure you haven’t missed anything. It will make you more confident and secure in your conclusions, and keep you from constantly having to backtrack to verify information.

Disproving Is Easy, Proving Is Hard

In many cases, disproving something is much simpler than proving it.

Is your friend actually descended from King Edward V?

Not likely.

Ten seconds on Google will tell you that Edward V was never married and died when he was 12.

Proving facts and connections when you don’t have direct evidence is tough, but the GPS is there to help you and guide you through the process.

Additional Reading

This guide was written to give you some baseline knowledge of the GPS and how important it is to use in your research.

To learn more, I encourage you to pick up a copy of Genealogy Standards written by the Board for Certification of Genealogists.

I also highly recommend reading Mastering Genealogical Proof by Thomas Jones and Evidence Explained by Elizabeth Shown Mills.

Sources

Board for Certification of Genealogists. Genealogy Standards. 50th Anniversary Edition. Washington, D.C.: Ancestry, 2014.

Jones, Thomas W. Mastering Genealogical Proof. Arlington, Virginia: National Genealogical Society, 2013.

Shown Mills, Elizabeth, editor. “Professional Genealogy”: Preparation, Practice & Standards. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2017.

Shown Mills, Elizabeth. Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace. Third edition. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2017.

Hello, Marc! Thank you for this very thoughtful, well formatted article and the easy to follow flow chart. What great information for a person new to genealogy, wanting to do things correctly from the very start! Your site is a gold mine.

I happened to find your GPS article while I was searching for inferential genealogy and Dr. Thomas W. Jones’ correlation work. You have helped me immensely. I’m writing a short non-fiction article to complete an assignment for Institute for Writers. I’m asked to use quotes in the article. Is it agreeable with you if I refer to your article and use your name? My email address is below.

Sincerely

Sure thing! And good luck with your article.

I’m working on brick walls in my husband’s family: both maternal and paternal lines have individuals born in the 1800s with no documentation of their fathers. A lot of what I’m looking at now is DNA evidence. Do you have a GPS that integrates using DNA evidence? In my own family, I was finally able to confirm the identity and lineage of my great grandfather who came to the US from Norway in 1868 and promptly anglicized his name. Based on all the paper documents, I had identified a candidate in Norwegian records but was not getting any understandable DNA connections to his family and the documents generally fit what I knew but certainly couldn’t meet the GPS to ‘claim’ this particular Norwegian for my tree. It’s tough when you’re dealing with patronymics, in my case Jens Andersen born about 1850 in Oslo. But it finally happened (tested 5/2015, breakthru 3/2019) and I now have solid documentary evidence that meets the GPS as well as many cousins in Norway! As I look to these other challenges I feel every bit the amateur that I am and would appreciate your insights.

Hi Pat. Sorry for the late reply but the new version of the BCG standards includes DNA. You can find those new standards here: https://amzn.to/3ewngRC

I requested the poster but haven’t received it in my inbox.

I would really love to have this on my wall!

Hi Carrie. Can you check out spam box? If it’s not there let me know and I’ll send it direct.

I’ve been researching my family for nearly forty years. I collect ALL information in each county and state, sorted by State-County-Date, I add sources with footnotes, when I add each record I type each document in verbatim, I have THOUSANDS of copies of ORIGINAL documents, wills, deeds, probate-successions, Bible, Military, Census, Church, etc.

When I send out information, they can see for themselves what each document contains.

One important note: nearly EVERY mother remembers the exact time and day and month she gave birth, years later, but I have found in many instances the mother could NOT remember the YEAR their own child was born. Bibles are GREAT sources, but don’t take them for granted.

Yes. Cross-reference EVERYTHING

Documents are essential, and are best when done in the correct order,

Excellent companions to the above excellent document:

The Evidence Analysis Process Map

https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-17-evidence-analysis-process-map

Genealogy Research Process Map:

http://www.thinkgenealogy.com/wp-content/uploads/Genealogy%20Research%20Map%20v2.pdf

Navigating Research with the Genealogical Proof Standard – July 2009 [90 slides]

http://www.slideshare.net/marktucker/navigating-research-with-the-genealogical-proof-standard-july-2009

Thanks, Brian!

I requested the poster, but it never made it to my inbox. But I right-clicked the image and selected “Save image to” and got a jpeg on my computer, 10 x 14. This is big enough and handy enough for my purposes.

Sorry about that, Ted. Let me know if you still need the larger one. Right-click and save will get you the low res version. For print, you’ll want the high res version instead.

Your generous knowledge sharing with all us budding genealogists is an excellent example of how the profession will continue to grow and improve. I hope we all pay it forward.

Thank you.

Very interesting to work with the chart

Hi genealogyexplained,

May I have your permission to post your process flow chart reference graph in our Family History Center? Visuals raise the bar for quality research, and this is fabulous!

Yes, please feel free. I’m also working on a printable poster-size version which should be available later this week.

The poster file is now available! See the download form below the image.

I think this would make a great poster as a reminder for everyone that a wiggling leaf is not a “proof”. 18 x 24 and 24 x 36?

Thanks Robin, I am looking into this.

Sorry for the shouting, but I am a stickler for giving credit where credit is due. 🙂

WITH YOUR PERMISSION, and a clear image people can go to almost any office supply company and print their own poster. I just looked at Staples and not only can an online order be placed, there are also options to laminate and even add an easel in case someone wanted it free standing!

I am very impressed. I have been doing my family history for 6 + years now and am still learning so much. Thank you for this article, very very informative.

I agree, please offer posters. Not overly large for my needs, just sturdy.

Sweet!

Thank you for this graph and the explanation. I have seen to many bits of “research” that don’t follow through even the first few steps but are taken as truth. I need to do better at citations and research logs myself, but I do try to make sure my trees, online or offline, have a fairly comprehensive proof behind every name attached.

Is there a way to get a clearer copy of the flow chart. The copy I made from the site is blurry and hard to read.

Hi Joseph. Click on the image to enlarge. It should be much clearer.

Is this available for purchase as a poster? I use genealogy research to teach students history and analysis skills. It would be a great resource.

Hi Pam. It’s not available as a poster. But that’s something I should look into if there’s enough interest. What size poster would be ideal for your needs?

I so wish I had found your site before I had started my search as I would have kept better records of how, where and when I found records pertaining to my family.

I look forward to reading more on this site.

Thank you, most informative.