A Harvard professor discovered something shocking in her Civil War history seminar.

When she showed students photographs of original Civil War manuscripts, about two-thirds of the class couldn’t read them.

Not because the handwriting was messy. But because they couldn’t read cursive at all.

Two-thirds.

Let that sink in.

This isn’t an isolated incident.

It’s a generational shift.

The Numbers Tell the Story

In 2010, everything changed.

The Common Core State Standards dropped cursive from national K-12 requirements. Instead, they mandated that fourth graders “demonstrate sufficient command of keyboarding skills to type a minimum of one page in a single sitting”.

No mention of cursive.

Within three years, 41% of elementary teachers had completely stopped teaching cursive.

The dominoes fell fast.

Today? Educational researchers estimate that approximately 50% of children in K-12 education haven’t received any instruction in reading or writing cursive.

Half of American kids.

The National Archives now actively recruits volunteers who can read cursive in order to transcribe and digitize their backlog of records.

They refer to cursive as an increasingly rare “superpower.”

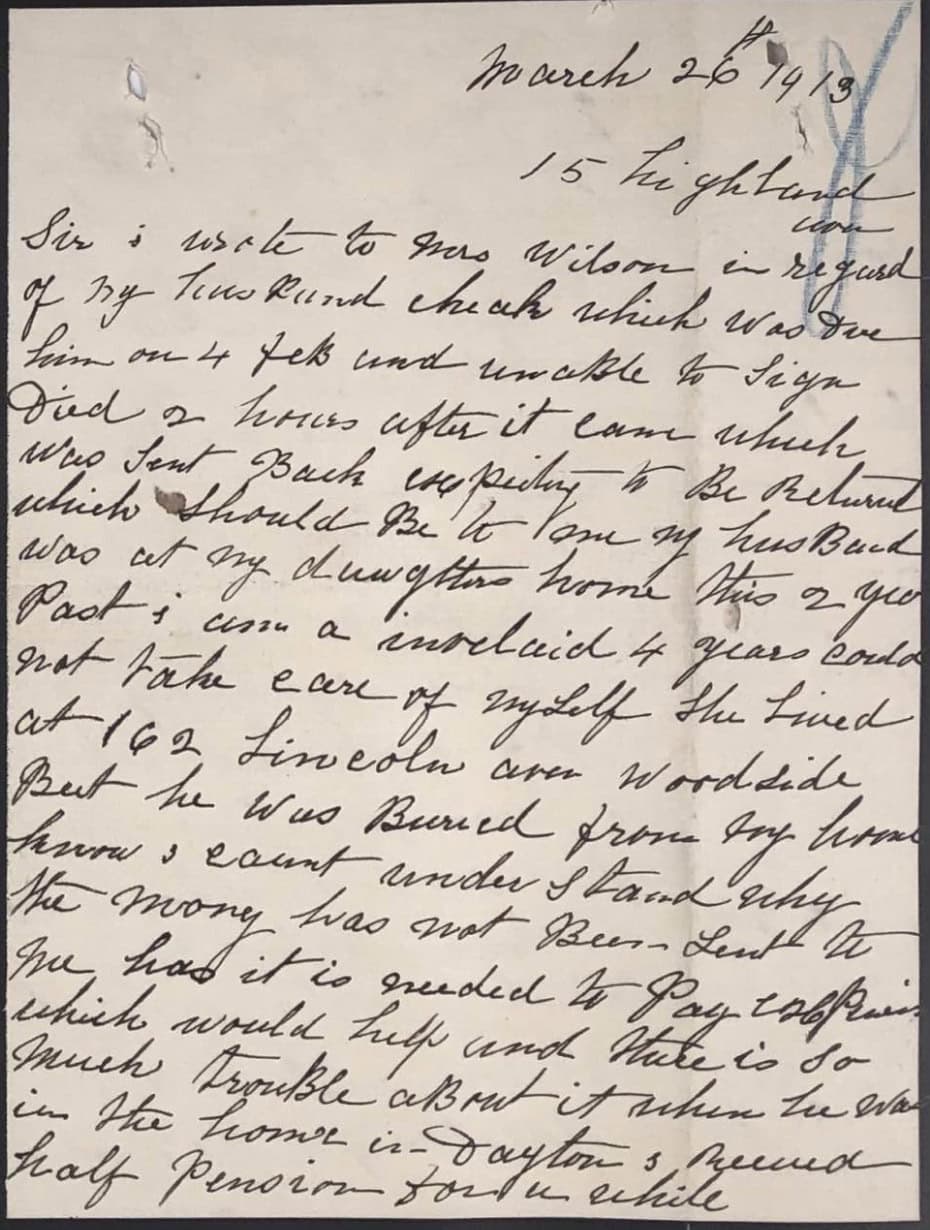

Test Yourself. Can You Read This?

This is a letter from my Great-Great-Grandmother.

She wrote it after my Great-Great-Grandfather died. He passed away 2 hours after his Civil War pension check arrived.

He never got to sign it.

Now she can’t afford his coffin.

Look at what this single page reveals:

- The exact moment of family tragedy (February 4th, check arrives, death follows)

- His journey through old age (soldier’s home in Dayton, then daughter’s house for 2 years)

- Multiple addresses (her home, daughter at 162 Lincoln Ave Woodside, the Dayton soldier’s home)

- Her disability (“invlaid 4 years could not take care of myself”)

- How families survived (soldier’s homes, half pensions, living with children)

- The rawness of grief mixed with bureaucratic frustration

- A woman’s desperation hidden in misspellings and run-on sentences

If I couldn’t read cursive, I would have lost:

- My great-great-grandmother’s voice.

- Her struggle.

- The fact that she couldn’t care for herself but still fought for what was owed.

- The knowledge that my great-great-grandfather was a veteran who lived in a soldier’s home.

- The address where my family once lived.

- The understanding that even after serving his country, his widow couldn’t afford his burial.

- The revelation that the pension system failed them at the worst possible moment—2 hours that changed everything.

The next page of this letter (not pictured here) goes on to say that his “creeping paralysis got the best of him” (referring to his death).

Contrast that to his official death certificate which lists his cause of death as ‘old age.’

Without records like this, I would have lost their story.

And with it, part of mine.

The Classroom Crisis

Students are reshaping their academic careers around this limitation.

One student changed his senior honors thesis topic to avoid manuscripts. Another abandoned her interest in Virginia Woolf because she couldn’t read Woolf’s handwritten letters.

Here’s what’s worse: professors write feedback in cursive. Most students can’t read it. They either ask for translation or ignore it completely.

Wasted effort.

Alex Heck, 22, tried reading her grandmother’s journal after she died. She and her cousin attempted to decipher it “like one might a code,” passing passages back and forth.

“It was kind of cryptic,” Heck said. “I’m not used to reading cursive or writing it myself”.

Family history. Lost in translation.

The State of American Handwriting

Recent data paints a troubling picture.

45% of Americans struggle to read their own handwriting. 70% have trouble reading notes from coworkers. Yet 86% of adults still write things down for organizational purposes.

We write. But increasingly, we can’t read what we write.

Students who learned cursive report they “rarely use it and seldom read it”. The skill atrophies without practice.

Even handwriting teachers are abandoning pure cursive. A 2012 survey at a Zaner-Bloser conference found only 37% of handwriting teachers primarily wrote in cursive. 8% printed. The majority—55%—used a hybrid style.

If the teachers don’t use it, why would students?

The Science Is Clear

Brain research reveals why this matters.

Studies from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology show handwriting links to better brain function, memory, and motor skills.

When children form letters by hand, brain scans show neural circuitry lighting up in ways that don’t happen with typing.

Each handwriting style—print, cursive, and typing—creates distinct neurological patterns.

Cursive may activate both brain hemispheres simultaneously.

Virginia Berninger’s research at the University of Washington found cursive had “measurable positive effects on older children’s spelling and composition skills”.

Why?

The connected letters may help the brain see words as units, not just letter collections.

Kelsey Voltz-Poremba, occupational therapist at the University of Pittsburgh, explains that physically forming letters helps “imprint” them in the brain, making learning the alphabet and reading “significantly easier for children”.

Note-taking research supports this. Students who take notes by hand process information better than laptop users. They can’t transcribe verbatim. They must summarize and reframe.

The result? Better retention.

States Fight Back

Recognition of this crisis has triggered a reversal.

In 2016, only 14 states mandated cursive instruction. By 2024, that jumped to 23 states. Maine just became the 25th in 2025.

The current list: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

California’s Governor Gavin Newsom signed cursive requirements in October 2023. Kentucky’s Governor Andy Beshear signed SB 167 in 2024.

More states have pending legislation. Pennsylvania introduced a bill in December 2023. New York and New Jersey are considering similar measures.

Louisiana’s state senators unanimously voted to restore handwriting instruction while crying out “America!”—reminding constituents the Declaration of Independence was written in cursive.

But implementation varies wildly.

Some states require cursive through fifth grade. Others stop at third. Some test proficiency.

Others don’t.

What We’re Actually Losing

Jimmy Bryant, director of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Central Arkansas, asked his class who wrote in cursive to communicate.

None did.

“A connection to archival material is lost when students turn away from cursive,” Bryant observed.

The practical implications multiply.

Historical documents become inaccessible. Family letters remain unread. Signatures devolve into “creative squiggles and flourishes” mixing “vestiges of whatever cursive instruction they may have had”.

Even the SAT noticed. Only 15% of students wrote the essay portion in cursive in 2007. Yet both the SAT and ACT require students to copy a paragraph in cursive—not print—causing confusion in test rooms.

Sandy Schefkind, a pediatric occupational therapist, argues that cursive develops fine motor skills: “It’s the dexterity, the fluidity, the right amount of pressure to put with pen and pencil on paper”.

Some students with dyslexia find cursive easier than print because the connected letters reduce reversals like ‘b’ and ‘d’.

The Technology Argument

Critics say cursive is obsolete.

Students now use talk-to-text and AI for writing. Some professors report identifying AI-written work because it “lacks punctuation and resembles a stream of consciousness”.

Fair point.

But we still teach math despite calculators. We teach reading despite audiobooks.

Why abandon handwriting because of keyboards?

Technology should expand capabilities. Not replace them.

The Path Forward

This isn’t about perfect Palmer Method penmanship.

Research suggests 10-15 minutes of daily practice suffices. Focus on legibility, not perfection.

For parents: investigate your school’s curriculum. If they don’t teach cursive, resources exist. Workbooks. Apps. Online programs.

For educators: consider the evidence. Handwriting instruction supports literacy development. It strengthens neural pathways. It preserves historical access.

Richard Christen, professor at the University of Portland, admits the practical argument for cursive is weak. But he mourns something else: “These kids are losing time where they create beauty every day”.

The Bottom Line

We’re witnessing a massive shift.

Is this evolution? Or are we creating barriers to our own history?

Twenty-five states say it’s a problem worth solving.

The rest? Still deciding.

But when college students can’t read the Constitution in its original form, when grandchildren can’t decipher their grandparents’ letters, when historical research becomes impossible without intermediaries…

We’ve lost more than a writing style.

We’ve lost a connection.

And that connection, once severed, is hard to restore.

Sources and additional reading:

- Gen Z Never Learned to Read Cursive by Drew Gilpin Faust

- The Case for Cursive by Katie Zezima

- What We Lose With the Decline of Cursive by Tom Berger

- The 25 States that Require Cursive Writing [Updated!]

And it took a Harvard Professor to figure it out! That shows how smart they are (HaHa). I just completed High School, and could tell you years ago, if the children are not taught something, the want know how to do it. Been doing genealogy 47 years and have gotten pretty good at reading cursive from 17th and 18th century.

Thank you! As a retired teacher of handwriting, and as a genealogist who reads cursive in several languages, I applaud your efforts to bring back the Sharon Troy Centanne study of cursive to all classrooms. Cursive is essential, especially for historical research!