Your grandma’s kitchen smelled different than yours does.

Not just the cigarette smoke and Aqua Net. The food itself was different.

These weren’t Instagram-worthy dishes. They were survival foods that became tradition. Foods that fed families through depressions, wars, and Wednesday nights.

Every weird dish your grandma served tells a story. About where your family came from. What they could afford. How they survived.

Here are 10 foods that were on every grandma’s table—until they weren’t.

1. Head Cheese (Sülze/Fromage de Tête)

Let’s start with the elephant in the room. Or rather, the pig’s head in the pot.

Head cheese isn’t cheese. It’s everything from a pig’s head boiled down, picked clean, and suspended in its own gelatin.

Sounds gross?

Your great-grandparents called it resourceful.

Every immigrant family made this.

Germans called it Sülze. French called it fromage de tête. Poles had their own version. The name your family used opens a window into their past.

The recipe varied wildly. Some added vinegar. Others threw in wine. Some kept it simple with just salt and pepper. Others added herbs that grew in their gardens. The variety was endless.

This was “waste nothing” cooking at its finest.

When a pig cost two months’ wages, you used every part.

Even the oink.

2. Aspic Everything

Tomato aspic ruled every church potluck from 1920 to 1975. Then it vanished.

Walk into any mid-century social gathering and you’d see them. Shimmering molds of suspended vegetables. Translucent towers of tomato jelly. Entire salads encased in crystal-clear gelatin.

Why did grandma suspend everything in jello?

The story starts with bones.

Before commercial gelatin, making aspic took all day. Calf’s feet boiling for hours. Constant skimming. Straining through cloth. Clarifying with egg whites. One wrong move and you’d have cloudy, greasy soup instead of crystal-clear jelly.

Only fancy restaurants and wealthy households bothered.

Then Charles Knox changed everything. In 1890, he figured out how to granulate gelatin. Suddenly, anyone could make aspic. Just add water. No bones. No boiling. No skill required.

But the association with wealth stuck.

Aspic meant you had time for fussy cooking. Money for unnecessary ingredients. The knowledge to make “sophisticated” food. It was culinary social climbing in a mold.

By the 1950s, every housewife had a collection.

Copper molds shaped like fish. Aluminum rings for crown salads. Ceramic molds passed down from mother-in-law. Each one polished before use. Each one producing Instagram-worthy dishes decades before Instagram.

The recipes got competitive. Church cookbooks from the era read like aspic Olympics. “Perfection Salad” competed with “Sunset Salad.” “Emerald Ring” battled “Ruby Red Mold.” The names alone tried to out-fancy each other.

Some families had signature combinations.

Lime jello with cottage cheese and pineapple. Tomato aspic with shrimp and celery. Lemon gelatin with cabbage and carrots. Combinations that sound insane now but represented sophistication then.

The ingredients tell stories. Canned fruit cocktail appears constantly—shelf-stable luxury. Mayonnaise gets folded into everything—refrigeration was still new for many. Cream cheese when you had money. Cottage cheese when you didn’t.

Those elaborate molds in grandma’s basement aren’t just kitchenware. They’re artifacts of aspiration. Of women trying to elevate everyday ingredients into party food. Of turning cheap proteins and leftover vegetables into architectural wonders.

The trend died when natural foods took over. When Julia Child taught us about French cooking. When suspended vegetables started looking dated instead of elegant.

But check any estate sale. Those molds are still there. Waiting. Holding the shape of different dreams.

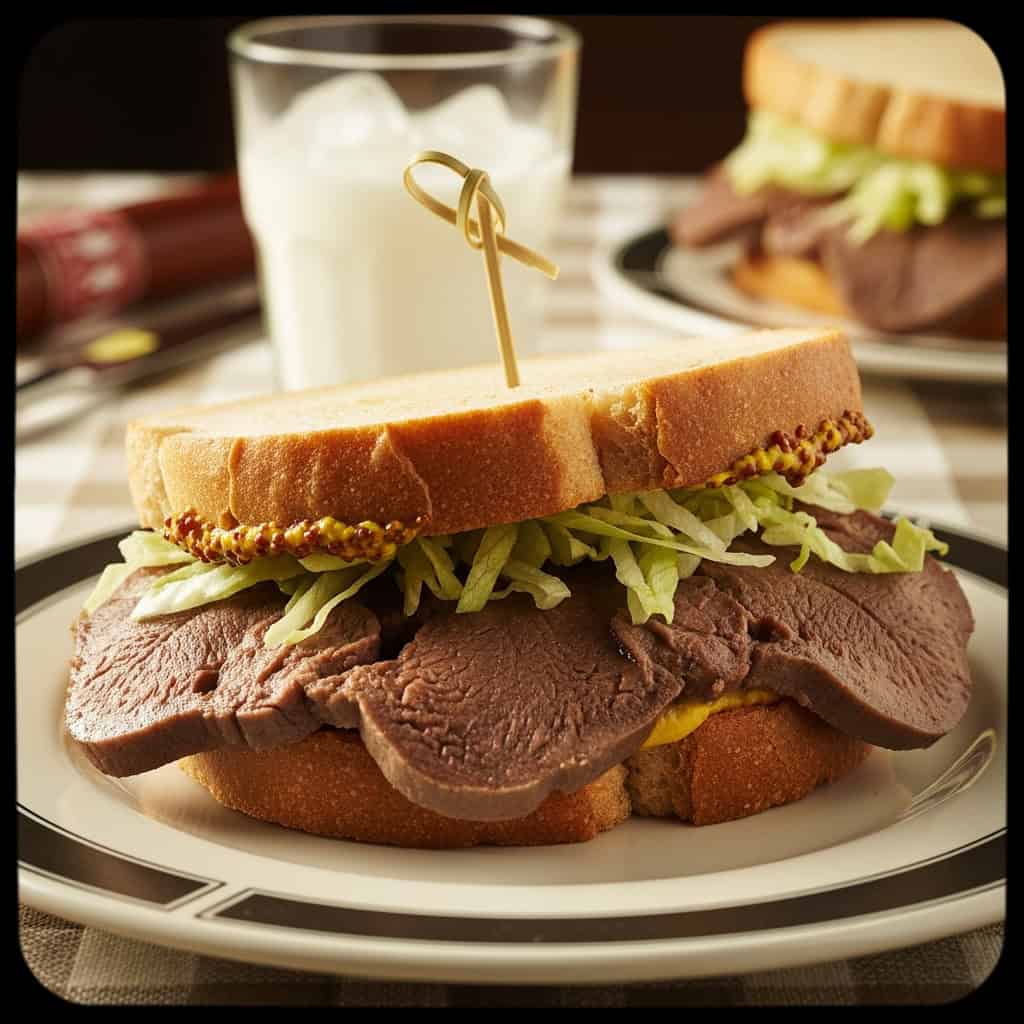

3. Tongue Sandwiches

Your grandpa’s lunch bucket had tongue in it.

Not an insult. Actual tongue. Beef tongue was working-class gold. Cheap, filling, and available at every corner deli. Jewish delis served it with mustard. Mexican families braised it for hours. German butchers smoked it. Italian grandmothers simmered it in tomato sauce.

Until it wasn’t available anymore.

The preparation took patience. First the simmering. Then the peeling. That outer skin had to come off while hot. Timing was everything. Too cool and it stuck. Too hot and you burned your fingers.

Every family had their method.

Some soaked it in brine first. Others went straight to the pot. Some sliced it thick for sandwiches. Others thin for cold plates. The leftovers went into hash or grinding for sandwich spread.

Find tongue in a family recipe box? Look at the other recipes around it. Organ meats traveled together. Liver, kidneys, heart. These were the proteins of the working class. The ones the butcher saved for regular customers. The ones that required skill to make delicious.

Tongue disappeared when we got squeamish. When meat started coming in styrofoam packages. When we forgot that our ancestors couldn’t afford to waste anything edible.

The delis that sold it closed one by one. The butchers who saved it for regulars retired. The grandmas who knew how to cook it stopped teaching the recipe.

4. Scrapple/Livermush

Call it scrapple in Philadelphia. Livermush in North Carolina. Goetta in Cincinnati.

Same idea: take the scraps, add grain, make it last.

Pennsylvania Dutch made it with everything but the squeal. After butchering, every scrap went into the pot. Meat picked from the head. Bits trimmed from the organs. Everything too small to cure or grind. Add cornmeal or buckwheat. Cook until thick. Pour into loaf pans. Slice and fry for breakfast.

The grain varied by region and availability.

Cornmeal dominated in areas where wheat was expensive. Buckwheat appeared where it grew wild. Oats showed up in some recipes. Steel-cut, not rolled. Each family had their proportion. Their secret ingredient. Their way of seasoning.

Some added sage. Others preferred marjoram. Black pepper was universal. Red pepper appeared in some regions. Bay leaves in others.

The texture ranged from smooth to chunky. Some families ground everything fine. Others left identifiable pieces. “You should see what you’re eating,” one grandma said. Another preferred it “smooth as butter.”

Scrapple traveled with families as they moved west. The recipe adapted to new ingredients. New grains. New seasonings. But the principle remained: waste nothing, stretch everything.

Your family’s scrapple recipe is a historical document. The ingredients tell stories. The proportions reveal economics. The seasoning preferences track through generations.

5. Blood Sausage/Black Pudding

Every culture had blood sausage. Every. Single. One.

Blutwurst. Boudin noir. Morcilla. Black pudding. Kiszka. Hundreds of names for the same principle: blood is protein, don’t waste it.

The process happened on butchering day. As soon as the animal was killed, someone caught the blood. Mixed with vinegar or salt to prevent clotting. Then the real work began.

Some added rice. Others used barley. Onions were universal. After that, every family diverged. Some added cream. Others stuck with chunks of fat. Apples appeared in some versions. Raisins in others.

The casings mattered too.

Natural casings from the same animal were traditional. But they required cleaning. Soaking. Scraping. More work than many wanted to do. Some families switched to cloth bags. Others formed patties instead.

This disappeared after WWII. Refrigeration made preservation less critical. Supermarkets offered convenience. The generation that made it didn’t always pass it down. They wanted their kids to fit in. Blood sausage marked you as different. Foreign. Poor.

But the recipes survived in handwritten notes. In church cookbooks. In the memories of kids who watched their grandmothers work. Each recipe slightly different. Each one a piece of family history.

6. Pickled Everything

Open grandma’s fridge in 1955. Jars everywhere.

Pickled pigs feet. Pickled eggs. Pickled herring. Pickled beets. Pickled green tomatoes. If it could fit in a jar, grandma pickled it.

This wasn’t quirky. It was survival.

Before reliable refrigeration, pickling preserved the harvest. The summer’s cucumbers became winter’s pickles. Fall’s green tomatoes became relish. Nothing went to waste.

The Great Migration brought pickling traditions north. Southern families carried their pickle recipes to Detroit and Chicago. Eastern Europeans brought their methods to Cleveland and Milwaukee. Every bar had gallon jars on the counter. Free lunch if you bought a beer.

The brine told stories.

Some families used straight vinegar. Others cut it with water. Sugar levels varied wildly. Some added it by the cup. Others just a pinch. The spices created signatures. Dill. Mustard seed. Coriander. Cloves. Each combination unique as a fingerprint.

Pigs feet required special treatment. First the cleaning. Then the splitting. Some families left them whole. Others cut them into pieces. The cooking time varied. Some liked them firm. Others falling apart.

Those jars were time capsules. Each recipe preserved more than food. They preserved techniques. Preferences. The taste of home.

The pickling tradition faded as refrigeration improved. As grocery stores stayed open year-round. As fresh became more valued than preserved. But the jars remained in basements. The recipes in boxes. Waiting.

7. Milk Toast

Every grandma had a milk toast recipe. None of them wrote it down.

Why?

Because everyone knew how to make it. Stale bread. Hot milk. Salt, pepper, butter. The end. This was sick food. Comfort food. Poor food. Sometimes all three at once.

But the variations told stories.

Some families toasted the bread first. Others used it stale from the box. Some poured the milk boiling hot. Others warmed it gently. Butter went on the bread for some, in the milk for others.

The additions varied by family. Sugar appeared in some versions. Just a sprinkle. Others added an egg, beaten into the hot milk. Some grated nutmeg on top. Others stuck with just salt and pepper.

The bread mattered too.

Store-bought white bread was common. But some used day-old bakery bread. Others made their own. The thickness of the slice changed everything. Thin dissolved into pap. Thick stayed chunky.

Milk toast was democratic. Rich and poor ate it. But presentation varied. Some served it in bowls. Others on plates. Some used the good china for invalids. Others ate it from coffee mugs standing over the stove.

This was the food of illness and poverty. Of late nights with sick children. Of empty cupboards before payday. Of old age when teeth failed. Every family had their version. Their way of making it special. Or at least edible.

The recipe died with the generation that needed it. Modern medicine replaced milk toast with Pedialyte. Food stamps replaced empty cupboards. Soft foods came in pouches, not bowls.

8. Creamed Chipped Beef on Toast

Aka “SOS” – Shit on a Shingle.

Every veteran knew this recipe. They learned it in the mess hall. Complained about it endlessly. Then came home and asked their wives to make it. Nostalgia is powerful.

The recipe was simple. Dried beef. White sauce. Toast. But every cook made it different.

Some rinsed the beef first. Others used it straight from the jar. The white sauce varied wildly. Some made it with butter and flour. Others used evaporated milk. Some added cheese. Others kept it plain.

It invaded suburban America through the GI Bill. As veterans bought houses, their wives learned military cooking. Church cookbooks filled with variations. “Company Creamed Beef.” “Deluxe Chipped Beef.” Each trying to elevate the basic recipe.

Regional variations developed fast.

Some added peas. Others threw in hard-boiled eggs. Mushrooms appeared in fancy versions. Pimientos in others. Some served it over biscuits instead of toast. Others over rice or noodles.

The brands evolved too. Armour dominated early. Then Hormel. Store brands appeared as supermarkets grew. Each had slightly different salt levels. Different textures. Cooks adjusted their recipes accordingly.

This dish tracked military service through families. The date it appeared in family recipe boxes. The variations used. The frequency it was served. All told stories about who served when.

9. Prune Whip

The dessert nobody admits to missing.

But every church cookbook had three versions. Because prune whip was health food disguised as dessert. Grandma’s generation was obsessed with being “regular.”

Let’s be honest. They were obsessed with pooping.

Prune whip was the solution. Dressed up with whipped cream and served in crystal. Made fancy with egg whites. Elevated with vanilla. But still, at its core, pureed prunes.

The recipe revealed class aspirations and economic status.

Fancy versions had egg whites beaten stiff. Cream whipped fresh. Real vanilla extract. Served in individual glasses. Garnished with nuts or candied fruit.

Basic versions used fewer eggs. Or no eggs. Some used evaporated milk instead of cream. Imitation vanilla. Served family-style from a big bowl.

The desperate got creative. Some recipes called for mayonnaise instead of cream. Others used whipped topping. Whatever stretched the prunes into dessert.

Find prune whip in your family cookbook? Look what surrounds it. It traveled with other “healthful” desserts. Carrot cake. Zucchini bread. Tomato soup cake. Anything that justified dessert as nutrition.

The presentation mattered as much as the recipe. Crystal dishes. Silver spoons. Lace doilies. All trying to disguise the medicinal purpose. Make it fancy enough and maybe the kids would eat it.

10. Mock Apple Pie

No apples. All Ritz crackers.

This is Depression cooking at its most creative. When apples cost too much, crackers and cinnamon could fool your brain. Chemistry and desperation combining into dessert.

The recipe appeared on Ritz boxes in 1935. By 1940, every family had their own version.

The basic recipe never varied much. Crackers. Sugar syrup. Lemon juice. Cinnamon. Baked until bubbly. But families made it their own. Some added vanilla. Others included lemon zest. Some dotted with butter. Others added a top crust.

But here’s the thing: families kept making it after the Depression ended.

Why?

Because it became tradition. Because grandma made it. Because it tasted like resilience. Because kids who grew up on it requested it. The fake became more real than the original.

The recipe survived in families that valued ingenuity. That remembered harder times. That taught their children to make do. Each generation passed it down with stories. “Your great-grandmother invented this.” “We ate this when times were tough.” “This got us through.”

Find mock apple pie in your family’s recipes? Look at the wear on the card. The stains. The notes in the margins. “Kids love this!” “Make for church social.” “John’s favorite.” These notes are biography.

Some families elevated it. Added cream cheese to the filling. Used homemade pie crust. Served it with real whipped cream. Others kept it simple. Store crust. Cool Whip. The variations tell economic stories across generations.

Your Kitchen Archaeology

These foods are primary sources.

Your great-grandma might have lied about her age, but her recipe collection tells the truth about her daily life.

Each recipe marks a moment in time.

Check the recipe cards. The condition tells you what mattered. Stained cards saw regular use. Pristine ones were aspirational. Multiple copies meant sharing with daughters and daughters-in-law.

Ask your relatives before it’s too late.

“Did grandma make head cheese?” opens more doors than “tell me about your childhood.”

Food triggers memory. Specific memory. The kind that includes great-aunt Ethel’s maiden name and why nobody talked to the Kowalskis after 1953. The kind that remembers which uncle wouldn’t eat blood sausage and why grandma made two kinds of pickles.

Your family’s weird food is your family’s real history.

Not the sanitized version. Not the Ellis Island story everyone tells. The actual, day-to-day, what’s-for-dinner history that explains how your family survived. What they valued. How they adapted.

That jello mold in the basement? That’s not junk.

That’s genealogy.

Start digging through those recipe boxes. Call your aunts. Visit the cousins who inherited grandma’s kitchen things. These recipes won’t last forever. The people who remember them won’t either.

But their stories will. If you preserve them now.