You’ve hit the genealogy wall. Names and dates aren’t enough.

The real stories—the lives your ancestors actually lived—are hiding in death records you’ve already collected but never fully examined.

Most researchers miss these crucial details. You won’t.

Here’s what you’re overlooking:

TLDR: Get my Hidden Clues in Death Records Cheat Sheet and stop missing the critical clues hiding in plain sight.

Death Certificates

Death certificates are genealogical dynamite. Most researchers skim them for dates and names, missing the explosive details that could obliterate your brick walls.

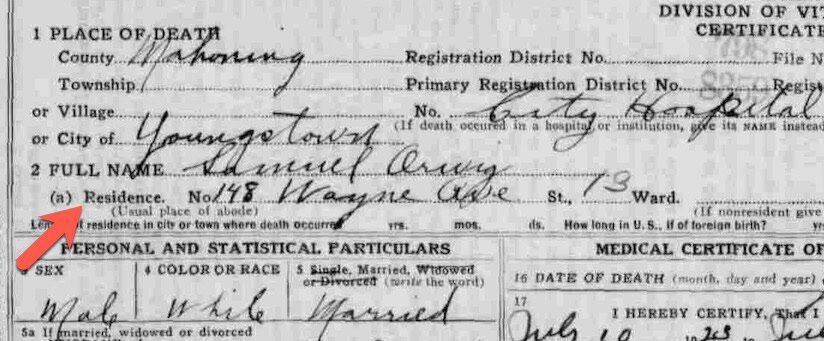

1. Residence at time of death. This single line can uncover hidden family dynamics and living arrangements.

Does it match the spouse’s address? If not, investigate why. Separation without formal divorce was common in eras when divorce carried stigma or was difficult to obtain.

My own 2x great-grandfather’s death certificate showed him living at a different address than his wife. When I traced that address, I discovered it belonged to his daughter. I later learned he had separated from his wife without a formal divorce—a family secret hidden for generations.

A hospital or nursing home address? Follow up. Admission records often contain next of kin information, detailed medical histories, and sometimes even personal effects inventories.

2. Unexpected death locations. Death far from a person’s residence raises immediate questions worth investigating.

Was your ancestor traveling? Visiting family? Working temporarily in another location? Perhaps they died during migration to a new home.

Newspaper accounts often cover deaths that occurred away from home, providing additional context not found in official records.

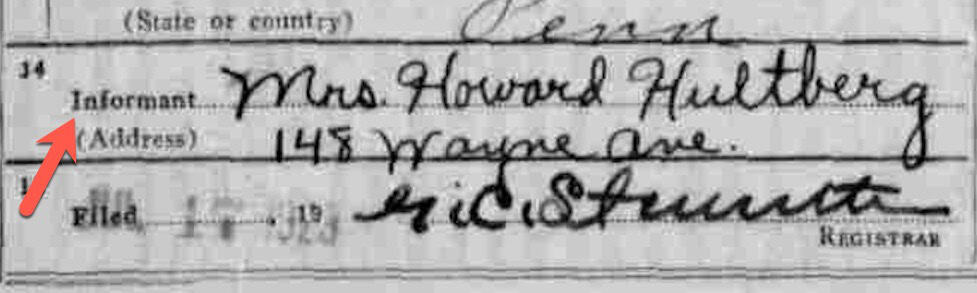

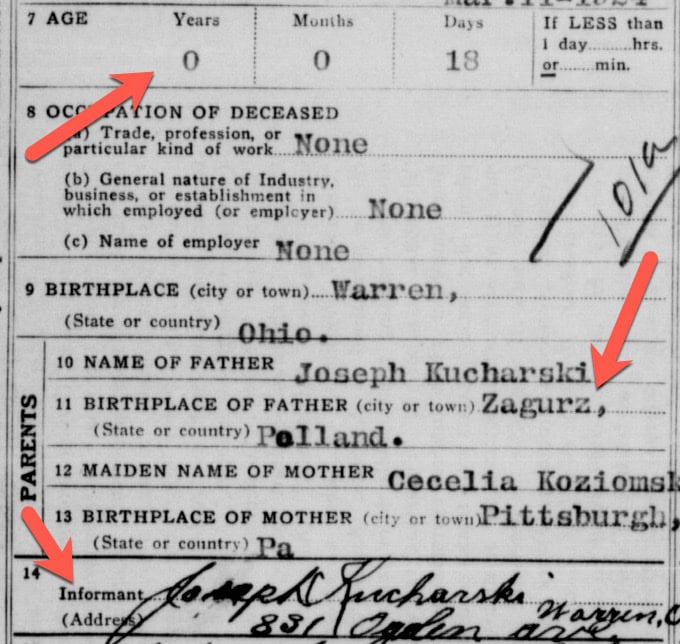

3. The informant’s identity. The person providing information reveals relationship networks and proximity.

A son-in-law as informant might indicate a closer relationship with that branch of the family. A landlord or employer suggests possible isolation or work-related circumstances.

Cross-reference the informant’s name with census records—they often lived nearby or were part of the same community network.

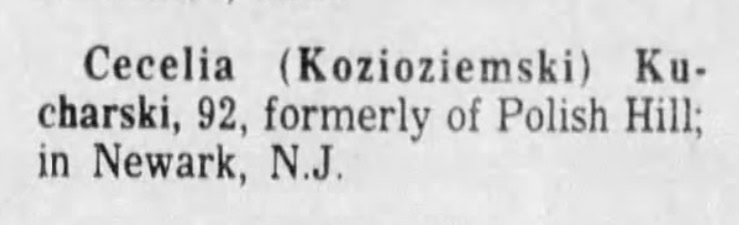

My other 2x great-grandfather died in City Hospital in Newark, NJ. The informant of the personal information was the hospital. There were so many incorrect facts on the death certificate that a corrected death certificate was issued. So always check this.

4. Place of birth details. Specificity matters. “Bavaria” versus “Germany” or “County Mayo” instead of just “Ireland” narrows your search significantly.

These details, while secondary information, are genealogical gold—they point you exactly where to look next. Just remember: they came from grieving relatives who might confuse details.

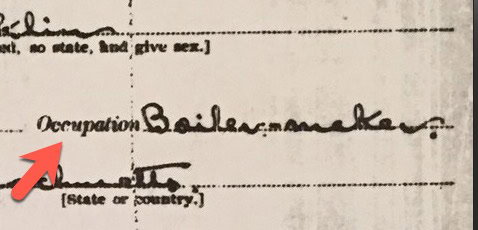

5. Occupation information. Your ancestor’s work reveals social class, education level, and potential hazards they faced daily.

Coal miners often died young from lung diseases. Factory workers faced industrial accidents. Certain professions clustered in specific neighborhoods.

Follow this thread to union records, company archives, or industry publications that might mention your ancestor.

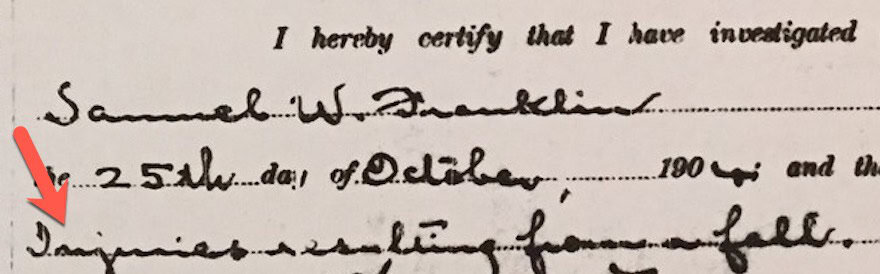

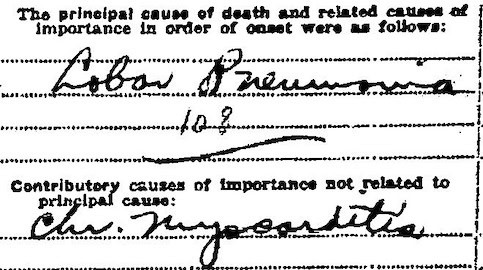

6. Cause of death context. Medical terminology tells social stories. Cholera suggests poor sanitation. Lead poisoning might connect to specific industries.

Epidemic diseases often wiped out multiple family members—check for other deaths in the family around the same time. Industrial accidents frequently led to newspaper coverage and sometimes compensation records.

7. Length of residence in the area. This overlooked detail creates timeline precision for your family’s movements.

Ten years in one location? Look for property records. Recent arrival? Check migration patterns for that time period and ethnic group.

Use this information to pinpoint exactly when your ancestor arrived in a location, helping you bridge census gaps and find them in city directories.

8. Medical details and duration. “Chronic” conditions meant long-term care from someone. “Sudden” deaths disrupted family structures without warning.

A lengthy illness often forced families to make difficult financial and living arrangements. Who provided care? Did other family members change occupations or move to accommodate the illness?

Contributing factors like alcoholism, malnutrition, or previous injuries tell stories about lifestyle, economic circumstances, or traumatic events.

9. Parents’ names and birthplaces. These details often come from children or spouses who may have heard the information directly from the deceased. Or have their own primary knowledge of the information.

If you find a child who died young and their immigrant parent is the informant, this is a fantastic source of primary information.

Don’t just look at your direct ancestors, look at their siblings as well.

Cross-reference with marriage records and other records, which might contain variations of the same information. Inconsistencies suggest family stories worth exploring.

For immigrant ancestors, parental birthplaces often reveal the specific old-world region, not just the country—critical for breaking through research barriers.

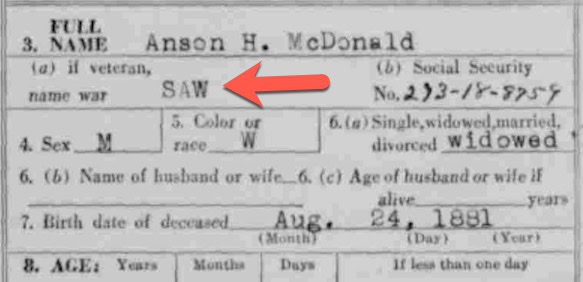

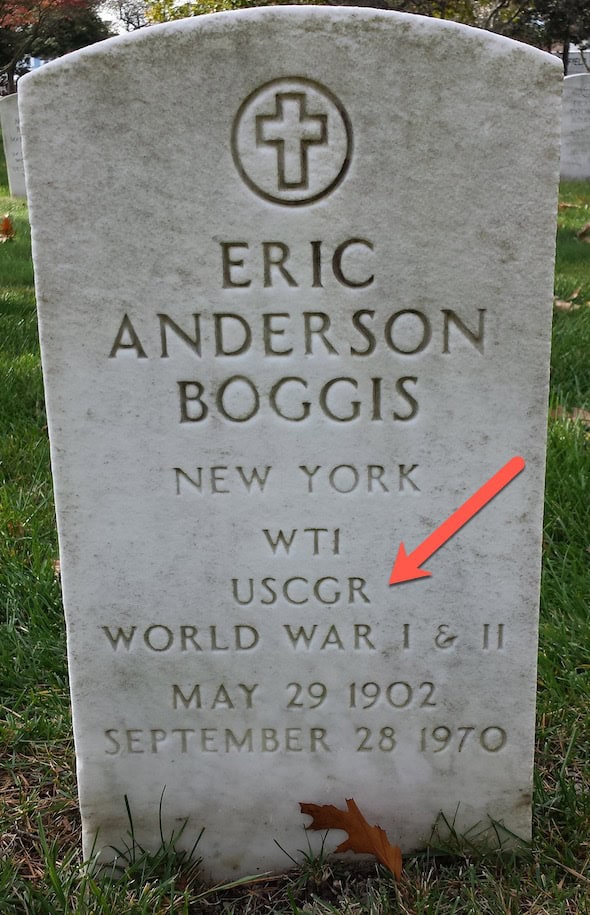

10. Military service indicators. These checkboxes or notes open doors to extensive military records.

Veterans’ death certificates might indicate service periods that help you locate draft registrations, unit histories, pension applications, and military hospital records.

Even brief military service generated paperwork that can reveal physical descriptions, literacy levels, and family circumstances.

11. Intentional omissions. Blank spaces tell stories. “Unknown” parents from an informant who should know might suggest family estrangement or secrets. Or just that the parents died a long time ago.

Compare what’s missing against what’s included. Did the informant know the father’s birthplace but not his name? That’s a clue to a story.

Privacy, shame, or family disputes often hide behind these blanks—and may appear in other records like court documents or newspaper accounts.

12. Marital status nuances. Beyond the checkboxes, look for inconsistencies and what’s left unsaid.

“Widowed” status is a multi-layered clue. First, it confirms your search for a spouse’s death record is warranted. Second, it narrows your timeline—the spouse died before this certificate was filed. Third, it suggests where to look—likely near where your ancestor lived unless migration occurred after widowhood.

“Widowed” but you can’t find a spouse’s death record? The spouse might have died in another jurisdiction entirely. Or look deeper—some “widowed” individuals were actually abandoned or separated, but claimed widowhood to avoid social stigma.

“Single” for an older person might indicate a lifetime of independence or same-sex partnerships not recognized in official documents. Or it could simply mean divorced/separated from spouse.

13. Coroner’s involvement and inquests. This indicates unusual circumstances requiring investigation—suicide, accident, crime, or suspicious circumstances.

Coroner’s records often contain witness statements, detailed scene descriptions, and testimony from family members not recorded elsewhere.

Local newspapers frequently covered inquests in detail, especially in smaller communities where such events were noteworthy.

Obituaries

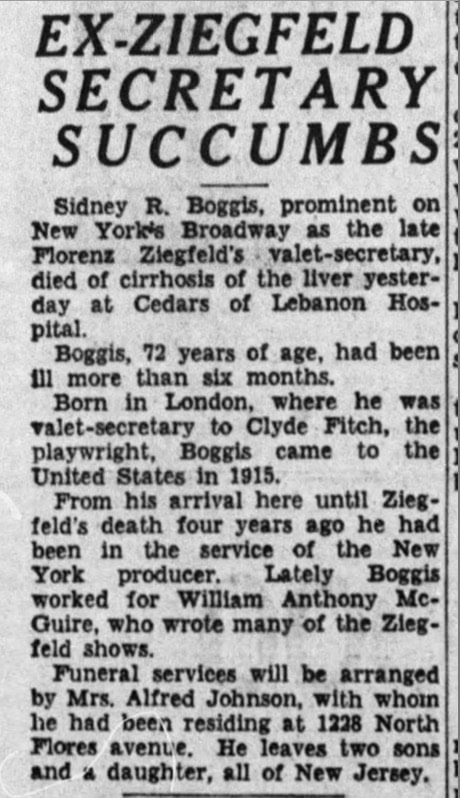

Obituaries aren’t just death announcements. They’re mini-biographies written when memories were fresh and family was gathered. Most researchers read them once and file them away—big mistake.

1. Survivors and predeceased relatives. These lists are family relationship gold. They document connections at a specific moment in time.

Pay attention to unusual inclusions or omissions. A niece listed prominently might have been raised by the deceased. A surviving spouse not listed as an executor suggests potential relationship strain.

Cross-reference survivor lists against census records to identify family members you might have missed. Predeceased relatives provide death date ranges to narrow your searches.

Extended relatives mentioned might be the only record of certain family connections, especially for women whose names changed through marriage.

2. Maiden names. Women’s birth surnames often appear in obituaries when they’re missing from every other record.

Even if your female ancestor’s maiden name isn’t directly stated, look for brothers listed with their surnames. This backdoor method reveals maternal lines that might otherwise remain hidden.

These names weren’t filtered through government clerks or census takers—they came directly from family who knew the correct name and spelling.

3. Religious and organizational affiliations. These connections open doors to entirely new record sets.

Masonic membership? Check lodge records. Catholic funeral? Parish death registers might exist. Legion Auxiliary? Organizational newsletters might contain tributes.

These affiliations reveal your ancestor’s social networks, values, and community standing—context you won’t find in vital records.

Religious affiliations may indicate where to look for baptismal, marriage, and other sacramental records. Fraternal organizations often maintained detailed membership files and provided death benefits.

4. Burial location details. Cemetery information leads to plot records, which often reveal who purchased the plot and who else is buried nearby.

Family plots tell stories—who’s included and who isn’t. Spouses buried separately? Children buried with grandparents? These patterns reveal family dynamics.

Cemetery records sometimes contain information missing from other sources, including relationships, payment records, and correspondence about the burial.

The choice of cemetery itself provides clues about religious affiliation, ethnic heritage, or community connections that might not be documented elsewhere.

5. Life details and employment history. Obituaries often mention jobs, businesses, or achievements that formal records missed.

Military service might list specific battles or theaters of operation. Career information might include companies long forgotten in family stories. Accomplishments might connect to newspaper articles published decades earlier.

These details point to specialized archives—company records, union documents, association minutes—that might contain additional information.

Career transitions, business partnerships, and employment periods create a timeline of your ancestor’s economic life. An obituary might mention a retired railroad worker spent his early years farming—giving you two occupation leads instead of one.

6. Current and former residences. Migration patterns revealed in obituaries help you track ancestors through time and place.

Previous residences listed in chronological order create a roadmap for your research. Brief mentions like “after moving from Iowa in 1932” narrow your search timeline dramatically.

Each location mentioned generates new research targets—city directories, land records, tax lists, and local histories specific to that place and time.

The sequence of relocations can explain gaps in census records or unexpected appearances in different states. Compare these locations with historical events—were they following economic opportunities, escaping hardship, or moving with extended family groups?

7. Immigration details. For immigrant ancestors, obituaries sometimes contain the only specific mention of origins or arrival dates.

Phrases like “came from County Clare in 1872” provide precision rarely found in census records. “Arrived as a child” explains why naturalization records might be missing.

Even vague statements narrow your search parameters and help focus your research efforts on specific regions or time periods.

Length of time in a country (“resided in America for 47 years”) lets you calculate arrival years which point you to immigration records. Original place names might be mentioned in obituaries when immigrants used more generalized terms on official documents.

8. Step-relatives and extended family. Obituaries often reveal connections that official records don’t categorize well.

Step-relationships, in-laws, and “chosen family” appear in obituaries when they’re invisible in government documents. An obituary might be the only record mentioning a child who died young in between census years or a relative who lived with the family briefly.

Look for phrases like “like a son to her” or “treated as a brother” that hint at non-biological but significant relationships.

Blended families become visible in ways census records might obscure. “Survived by his stepchildren” could explain why children in the household have different surnames, solving census puzzles you’ve struggled with for years.

9. Living arrangements. Subtle clues about housing situations appear in statements about where someone died.

“At his daughter’s home” suggests dependence or care arrangements in later life. “At the family homestead” indicates property that might have records attached.

These living situations often changed as people aged, creating shifting household compositions that census records (taken only every 10 years) might miss entirely.

Caregiving relationships reveal family bonds that transcend basic genealogy. An elderly parent living with a married daughter might have influenced that household in ways not captured by standard documentation.

Cemetery Records

Cemetery records aren’t just about location. They’re social maps revealing family connections, cultural heritage, and community structures that shaped your ancestors’ lives. Most researchers snap a headstone photo and move on. Major oversight.

1. Plot numbers and arrangements. These aren’t random. They tell relationship stories.

Adjacent plots often indicate family connections even when surnames differ. Multiple generations buried in precise arrangements reveal family hierarchy and relationships that might not appear in written records.

Plot numbers help you identify nearby graves that may belong to relatives you didn’t know about. Check cemetery maps and ownership records—families often purchased multiple plots together, even if some remained unused for years.

The orientation of graves, their proximity, and their arrangement can reveal family relationships that might not be documented elsewhere—unmarked children’s graves or relatives who aren’t mentioned in obituaries.

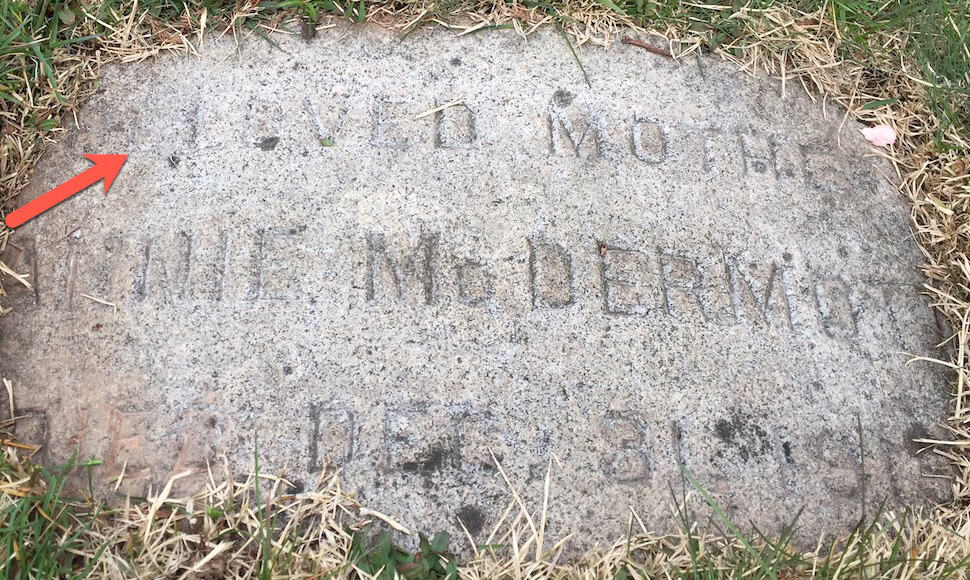

2. Grave markers and inscriptions. Beyond names and dates lies critical genealogical evidence hiding in plain sight.

Relationship designations like “beloved mother of” or “infant son” provide evidence of family connections. Terms of endearment suggest relationship quality. Epitaphs reveal personality, religious beliefs, or community standing.

Military insignia identify service periods, helping you locate military records. Fraternal symbols (Masonic, Odd Fellows, etc.) point to organizational records that might contain biographical information.

Multiple languages on a marker indicate cultural transition—the family maintained heritage while establishing American identity. Professional designations (“M.D.” or “Rev.”) lead to occupational records.

3. Cemetery sections and organization. The location within a cemetery can be as revealing as the grave itself.

Many cemeteries have separate sections for specific religious denominations, ethnic groups, or fraternal organizations. These divisions provide cultural context that might not be mentioned in written records.

Veterans’ sections indicate military service that might not be documented elsewhere, especially for conflicts with limited surviving records. Paupers’ sections reveal economic hardship that might explain family separations.

Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox sections indicate religious affiliation that can lead to church records. Segregated sections in older cemeteries document social structures that shaped your ancestors’ lives.

4. Unmarked graves and burial records. What you can’t see matters just as much as what you can.

Cemetery office records often contain information about unmarked graves, including names, dates, and sometimes even cause of death or next of kin—information that would otherwise be completely lost.

Burial cards or plot maps might show multiple burials in a single grave, revealing infant deaths or economic constraints. Payment records indicate who made arrangements, often a close relative with a different surname.

Temporary markers that disappeared decades ago are often documented in cemetery files. These records might be the only surviving evidence of children who died young or family members who couldn’t afford permanent markers.

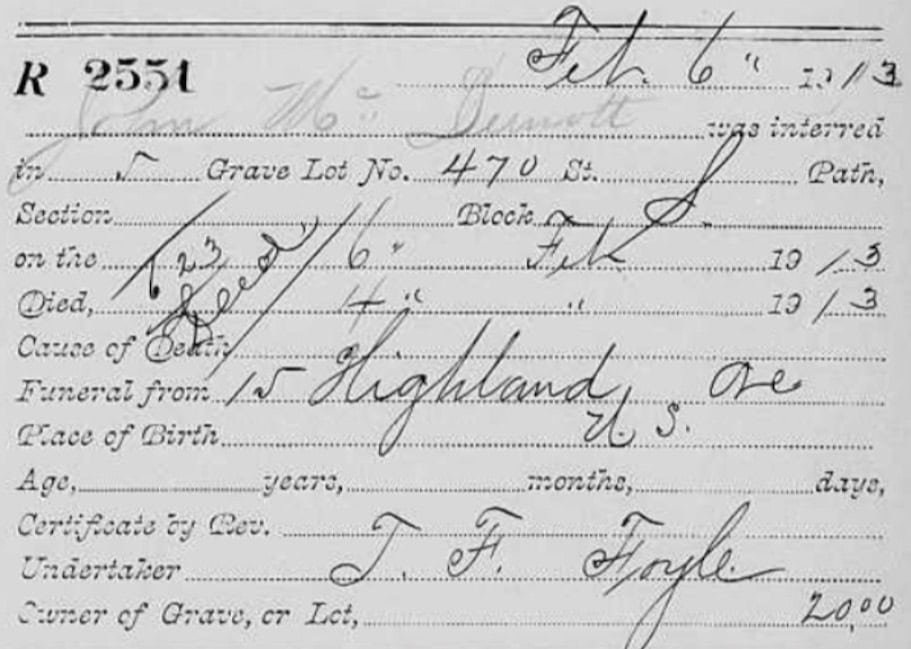

Funeral Home Records

These private business documents capture intimate details at a vulnerable moment when families reveal more than they ever would to government officials.

1. Next of kin information. This identifies who was closest to the deceased—legally and emotionally.

The person who arranged the funeral was typically a close relative or trusted friend. Their relationship to the deceased tells you who remained connected until the end.

Different relationships suggest different family dynamics. A son-in-law making arrangements might indicate the deceased was living with a daughter. A niece as next of kin might reveal childlessness or estrangement from children.

Contact details for the next of kin can lead you to addresses, phone numbers, and even occupations that don’t appear in public records. These details can help locate living relatives who might hold family information.

2. Funeral expenses and payment records. Financial details reveal economic status and family priorities.

The cost of the funeral relative to typical expenses of the era indicates financial standing. Was this an elaborate send-off or a modest affair? Each tells a different story about resources and values.

Who paid for what? Multiple family members contributing suggests shared responsibility. A single person covering all costs might indicate wealth disparity or particularly close bonds.

Payment plans or charity arrangements reveal financial hardship that might explain other family circumstances—migration patterns, living arrangements, or occupational choices driven by economic necessity.

3. Mourners and attendance records. Guest books and attendance lists document social networks frozen in time.

Names and addresses of attendees map the deceased’s community connections. People traveled from out of state? Those connections mattered.

Friends signing with the same address or workplace suggest social circles beyond family. Former neighbors attending years after a move indicate lasting community bonds.

Organizational representatives (unions, churches, clubs) document affiliations that might lead to other records. Special acknowledgments in guest books can reveal relationships not documented elsewhere.

4. Burial instructions and preferences. Pre-arranged details reveal personal values and family dynamics.

Specific requests about burial locations (“next to beloved wife Margaret”) confirm relationships and might suggest marriages not documented in surviving records.

Cremation versus burial reflects religious beliefs, cultural traditions, or personal philosophy—context for understanding your ancestor’s worldview.

Detailed instructions about clothing, jewelry, or religious rites provide insight into personal identity and values. Military honors requested tell you to search for service records even if family stories never mentioned service.

5. Transportation arrangements. These records document migrations and family connections across distances.

Bodies shipped for burial in another location suggest strong ties to former hometowns or family burial grounds. The logistics involved in such transportation created detailed records.

Transit permits required to move remains across county or state lines include death information that might differ slightly from official death certificates.

Arrangements for family members to travel from distant locations document where relatives lived at that specific moment—details often lost in the decades between censuses.

Probate Records

Probate records aren’t just legal documents. They’re family relationship maps, economic snapshots, and treasure maps to your ancestor’s entire life. Most genealogists only skim the index files and maybe read the will. They miss the entire probate file.

1. Heirs and beneficiaries. These lists identify family with precision that census records can’t match.

Probate documents name heirs in order of legal priority, creating a relationship framework that helps reconstruct families. The exact familial relationships are often explicitly stated: “daughter of my first marriage” or “son of my deceased brother James.”

Inheritance shares reveal family hierarchies and dynamics. Eldest sons receiving larger portions suggest traditional practices. Equal distribution among children suggests more progressive values, depending on the time period. Larger bequests to caregivers acknowledge unrecorded support relationships.

Excluded individuals raise red flags. A child conspicuously absent from a will might indicate estrangement, illegitimacy, or prior arrangements. These omissions create research paths to court cases, family disputes, or earlier gifts.

Conditional inheritances tell psychological stories. Funds held until certain ages suggest protection or control. Marriage requirements reveal social values. Educational provisions highlight parental priorities.

2. Estate valuations. The total worth and specific assets provide economic context.

Detailed inventories place your ancestor on the socioeconomic ladder of their community. Compare their worth to contemporary averages to understand their relative standing.

The mix of assets (cash, property, investments, personal items) reveals financial sophistication and priorities. Significant debt might explain family migrations or changed circumstances for survivors.

Real estate descriptions in estate inventories often contain boundary details and property histories more precise than deed records. Personal property lists reveal lifestyle, hobbies, and daily reality.

3. Debts and creditors. These financial relationships map community connections.

Lists of debtors show who borrowed from your ancestor—revealing business relationships, social networks, and economic standing. Who owed money to whom tells you who trusted each other.

Creditors listed in probate files identify businesses your ancestor patronized, medical care they received, and services they used in their final years. Each debt tells a story about daily life.

The nature and amount of debts provide context about financial circumstances. Were these business investments or desperate measures? Long-term arrangements or recent emergencies?

4. Guardianship appointments. Minor children required legal protection revealing extended family networks.

Guardian selections show who the deceased trusted most. Was it the expected choice (uncle, grandfather) or someone unexpected (family friend, distant relative)? Each choice tells a different story.

Guardianship bonds show who in the community vouched for these arrangements, identifying the deceased’s social network and those with enough financial standing to serve as guarantors.

Separate guardians for “person” and “property” suggest complex family situations or significant assets requiring financial expertise beyond what immediate family could provide.

5. Disputed wills and family conflicts. Legal challenges expose family dynamics otherwise hidden.

Contested wills reveal competing interests, family divisions, and sometimes previously unknown relatives. Look for affidavits from family members—they often contain birthdate evidence, relationship claims, and family stories.

Challenge reasons provide insights into family relationships. Claims of “undue influence” suggest caregiver relationships or possible elder exploitation. Mental capacity questions might indicate health issues not recorded elsewhere.

Multiple court appearances document family disputes, often containing testimony about relationships, shared history, and interactions not recorded in any other source.

6. Personal belongings and household inventories. These itemized lists reconstruct daily life.

Room-by-room inventories create floor plans of historic homes that may no longer exist. The quantity and quality of furniture indicates household size and economic standing.

Specialized items reveal occupations and hobbies that official records might miss. Tools indicate trades. Books show literacy and interests. Musical instruments suggest skills and leisure activities.

Clothing descriptions indicate social status, cultural connections, and sometimes health conditions. Heirloom items tracked through generations in wills create physical connections to earlier ancestors.

7. Business interests and occupational clues. Work-related assets reveal economic lives.

Inventories of tools, equipment, or professional implements provide occupational details beyond the generic labels in census records. “Farmer” in the census becomes “dairy farmer with 12 milk cows” in probate.

Business partnerships mentioned in probate documents identify associates who might appear in other records. Business debts and assets show whether enterprises were prospering or struggling.

Specialized inventories (farm equipment, shop tools, professional libraries) contain details about daily work life unavailable elsewhere. They help you understand what your ancestor actually did all day.

8. Appraisals and sales records. These documents name community members and reveal market values.

Appraisers were typically knowledgeable locals—neighbors, business associates, or relatives who understood the property’s value. Their names help map your ancestor’s community.

Estate sales list who purchased what, identifying neighbors, family members, and community connections. Items purchased by family members had sentimental value. Business tools purchased by colleagues suggest professional relationships.

The gap between appraised and sale values indicates market conditions or community support for the bereaved family. Items selling far above value might represent community members helping a widow or orphans.

Social Security Death Index (SSDI)

The Social Security Death Index isn’t just a death register. It’s a modern migration map, identity verification system, and family connection finder all rolled into one. Most researchers just confirm a death date and stop. Colossal mistake.

1. Last known residence. This single detail creates a research roadmap for your ancestor’s final years.

The last residence listed often differs from birthplace or mid-life locations, revealing final migrations. Elderly parents often moved near adult children—this residence might point to where other relatives lived.

Track this address to city directories, property records, and voter registrations to build a complete picture of your ancestor’s final chapter. Compare it to the address on the death certificate to identify short-term moves or institutional care not mentioned elsewhere.

Multiple addresses over time reveal retirement migrations, family caregiving arrangements, or economic necessity. Each address change tells a story worth investigating.

2. Social Security number. This nine-digit code unlocks geographical origins and leads to the genealogical jackpot.

The first three digits reveal where your ancestor applied for their Social Security card—not necessarily where they were born. This geographic clue can break research barriers for relatives who moved frequently.

Pre-1972 numbers were typically issued in the state of residence when the person first applied. Post-1972 numbers were usually issued in the state where the person was born or where their parents lived.

The complete SSN is your key to obtaining the SS-5 application—the holy grail of 20th-century genealogy. This application form contains the applicant’s:

- Full name (often including mother’s maiden name)

- Full birth date and place

- Parents’ full names

- Employer at time of application

- Residential address

- Signature

3. Birth date verification. This confirms identity and distinguishes between same-name individuals.

Compare SSDI birth dates against other records to resolve conflicting information. Discrepancies might reveal identity theft, administrative errors, or deliberate age modifications.

Birth date precision helps separate individuals with identical or similar names in the same region. The full birth date narrows newspaper searches and helps locate vital records in states with birth date restrictions.

4. Beneficiary information. These connected records reveal family support networks.

When you find a Social Security recipient, you can sometimes access information about who received survivor benefits—typically spouses and minor children. These connections document family relationships even when other records are missing.

Benefit applications contain verification documents—birth certificates, marriage licenses, children’s information—that family members may have submitted. These create research trails to vital records you might otherwise overlook.

Lump-sum death payment recipients (typically the person who paid funeral expenses) identify who handled final arrangements, often revealing the closest living relative or caregiver.

The SSDI isn’t just a death record—it’s the gateway to the most detailed personal document most 20th-century Americans ever completed.

The Story Hidden in Death Records

Death records aren’t endpoints. They’re starting points.

Every certificate, obituary, and probate file contains dozens of clues that most genealogists overlook. These aren’t just random facts—they’re breadcrumbs leading to the real stories of your ancestors’ lives.

The real power lies in connecting these clues across different record types. This is how you break through research barriers. This is how you transform names and dates into living, breathing people with stories worth telling.

Your ancestors were complex individuals who loved, struggled, succeeded, failed, and made decisions based on circumstances we can uncover—if we know where to look.

Death records contain the most intimate details of their lives. But only if you know how to extract them.

Get My Death Records Cheat Sheet

I’ve compiled all these insights into a printable cheat sheet that you can keep beside you during your research.

This isn’t just a checklist. It’s a roadmap to discovering the real stories behind your family tree.

👉 Click here to get your copy today and start discovering the stories hidden in the death records you already have.

What hidden stories will you uncover in your family’s death records?

The link for your death records cheat sheet doesn’t work.

thanks Jim Davis

Thanks for the heads up, Jim! Here it is: https://shop.genealogyexplained.com/hidden-clues-in-death-records/

Great article!

I found evidence I needed for a DAR application in an obituary not in the location of the woman’s death, but in her birth location. The obit started something like, “We received word that an old classmate has died in —————, —-, where she moved with her husband many years ago.” It went on to name her parents and her in-laws. Bingo!