I’m happy to have now released the 2023 data for the Forensic Genetic Genealogy Project. I began this project in the fall of 2020 so that I could systematically collect data on cases solved using the technique of forensic investigative genetic genealogy (FIGG) and create a registry – inspired by the National Registry of Exonerations, whose data I have worked with for many years now.

Here on Mendeley Data, you can find and download a copy of the database of cases solved, a case digest and bibliography of each case cleared, as well as a code manual which sets out my research methods and explains how I collect and code the data. Marc McDermott has kindly made much of this material available on the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Hub.

When I began this project, I wanted to make a contribution that would ensure that courts, regulators, policymakers, and fellow academics had reliable data on FIGG to inform their decision-making and to develop and govern this powerful new forensic tool.

2023 was a banner year – both for FIGG and for my project. Marc was good enough to host my case digests on his amazing website and make them searchable and accessible to the public. This has gone a long way to realizing the vision I had when I began this research. I also received funding for two wonderful students – Nico Concepcion and Taryn Mulvihill – to work with me this year updating cases and collecting data for further research into FIGG.

There were several important advances in the field this year. The Investigative Genetic Genealogy Accreditation Board (IGGAB) has made significant progress in developing its program to accredit AIGGs (Accredited Investigative Genetic Genealogists). The IGGAB’s mandate is to build public trust in the field, to set standards for ethics and competency for AIGGs, and to ensure accountability if an AIGG should fall below the standards. The IGGAB has now published the IGG Professional Standards and Accreditation Requirements, as well as the IGG Code of Professional Ethics, which you may access here. The IGGAB is working towards instituting an accreditation exam in 2024, and I will keep our readers up to date on these developments.

I am very grateful and honoured to have been made an Advisory Board member of the IGGAB. I look forward to lending what support I can to the IGGAB in the years ahead. Ensuring that practitioners uphold high standards of ethics and earn the trust of the public, the courts, and those who have provided their information to FIGG researchers, is vital for the field to reach its full potential as a professional forensic science.

The Case Solves

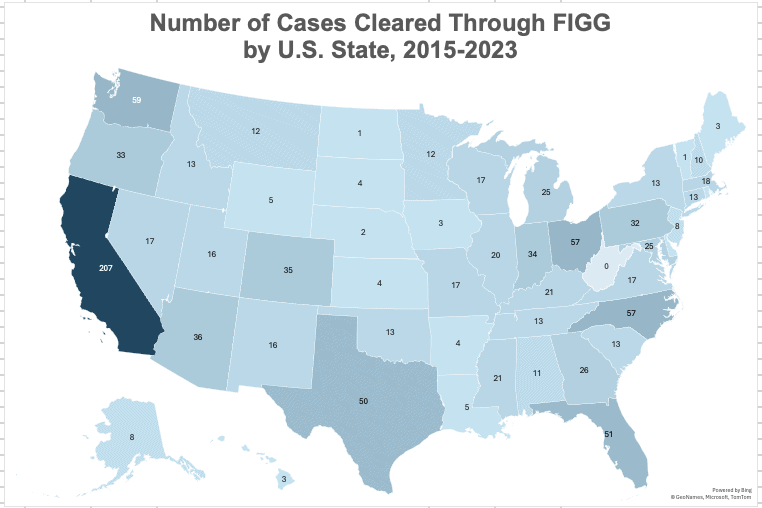

As of the end of 2023, there were 1130 recorded cases solved using FIGG – keeping in mind that I can only collect data on cases where the use of FIGG has been made public. This includes 651 criminal cases, 461 Does identified, 3 disaster victims identified, as well as 4 living Does.

A criminal case is defined as a victim-offender pair. Several of the perpetrators identified through FIGG were serial offenders – particularly serial rapes and rape-murders, which figure heavily in this dataset – 114 out of the 318 perpetrators identified through FIGG have more than one victim in the database, and several more have victims in cases that were cleared through other methods.

I’m asked more questions about this aspect of my research than any other: why don’t I just collect data on the offenders and leave it at that? This is one of the most important decisions I made – very early on in my research – and it’s had an enormous impact on how the project has shaped up. Defining cases as a victim-offender pair enables me to collect data that would otherwise be impossible, such as the relationship between victims and offenders (not surprisingly, most cases cleared through FIGG are stranger offences), as well as the source of the DNA sample (most samples used in FIGG investigations are semen from a sexual offence), as well as the charges laid and their disposition as they make their way through the various courts. It also enabled me to compare the data I collect with the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports.

Serial offenders have victims that are spaced out in time and place and sometimes cover several jurisdictions. One example is Clark Perry Baldwin. He was identified through FIGG and arrested in May of 2020 for the rape and murder of Pamela Aldridge McCall near Spring Hill, Tennessee. His DNA was then linked with two – very similar – murders in Wyoming: that of a young woman known only as ‘Bitter Creek Betty’, who was found on off Interstate-80 near the Bitter Creek turnout in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, and a pregnant woman known only as ‘I-90 Jane Doe’. She was found in April 1992, just off the Interstate-90 near Sheridan, Wyoming.

Each one of these is a separate case; each will wend their way through a different court in a different jurisdiction and may even have a different outcome. Data on each of these cases needs to be collected separately, which would be impossible if we only focused on offenders.

FIGG Around the World

By the end of 2023, cases had been solved in the USA (1087), Canada (28), France (5) and Sweden (2). 2023 also saw FIGG expand to Australia (7), and Norway (1), where a case was cleared in Oslo.

Criminal Case Solves by Decade

The oldest case solved is the identification of Richard Bunts, or Bunce (Case ID 1555), which goes all the way back to 1852. There are other cases of human remains being identified after 100 years, including the unusual case of Hallie Armstrong (Case ID 1419), who died in 1881 when she was just 18 years old. Her remains were found wrapped in old newspapers in a garage in New London, Ohio, even though she was supposed to have been buried in a grave at the Sugar Grove Cemetery. Another case is that of Joseph Henry Loveless (Case ID 1319), a bootlegger born in Utah in 1870 and whose remains were found in the Civil Defense Caves in Idaho. He disappeared shortly after escaping from jail in 1916, when he was arrested for the murder of his wife, Agnes Caldwell.

The oldest criminal case solved through forensic evidence is that of Kenneth Gould (Case ID 1488-1489), who murdered Duane Bogle and Patty Kalitzke in February of 1956. This is not the only homicide cleared from the 1950s either: John Hoff (Case ID 1557) was identified as the killer of 9-year-old Candy Rogers using forensic evidence collected in 1959. Both cases were solved by obtaining a DNA profile of the suspect from semen collected from the victims. Most criminal cases solved through FIGG have used semen as the biological source of the DNA profile.

And, yes, there have now been nine years of FIGG, which may surprise some readers! The first case solved through FIGG was that of Bryan Miller, also known as the Phoenix Canal Killer, who was arrested in January of 2015. The case was solved by Colleen Fitzpatrick, who used the Sorenson Y-STR database (now no longer active) to narrow down the pool of suspects and identify Miller. This case therefore represents a historic advancement in the field of FIGG. In June of 2023, Miller received two death sentences for the murders of 17-year-old Melanie Bernas and 22-year-old Angela Brasso, the only FIGG case to date to see a capital sentence handed down.

If you would like to know more about my research, you can download my original data on Mendeley, and you can read my paper in Forensic Science International: Genetics, here: Dowdeswell, Tracey Leigh. “Forensic Genetic Genealogy: A Profile of Cases Solved.” Forensic Science International: Genetics 58 (2022): 102679. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2022.102679.

Feel free to leave comments, or to provide further information on cases solved below. You may also access a copy of the FIGG Cleared Case Reporting Form here.

There’s so much more to say about these incredible cases than I can fit here. Soon, I will publish a recap of January 2024, and my take on the most amazing case solves of 2023. Stay tuned for all things FIGG!