February was busy, but not quite as busy as January 2024 for case solves. As of the end of February 2024, there are:

- 1182 cases cleared through FIGG;

- 332 suspects identified in criminal cases;

- 490 decedents identified;

- 3 disaster victims identified;

- 4 living does identified.

One of the highlights of February was the Institute for Genetic Genealogy’s I4GG Tenth Anniversary Conference, which was held in San Diego on February 10th and 11th. It was a wonderful presentation of case studies and key updates in the field.

Kevin Lord spoke about the DNA Justice database. DNA Justice is a non-profit agency that improves genetic privacy by having a dedicated database of genetic profiles uploaded solely for use in law enforcement investigations. Anyone can choose to download their DNA profile and upload it to DNA Justice here. Right now, there are 744 DNA profiles uploaded (including mine).

We also learned that the IGGAB – the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Accreditation Board – will be launching its accreditation exam later in 2024, along with an upcoming study guide. The exam will test prospective AIGGs on the core competencies of genetic genealogy, as well as communication and professional ethics. Those who would like to participate in beta testing may contact the IGGAB at [email protected]. The IGGAB practice standards and code of ethics may be found here.

Privacy issues in the field were also discussed at the conference. Barbara Rae Venter spoke about the use of FIGG in the investigation to identify Joseph DeAngelo as the Golden State Killer. She made the point that, over the decades when the case was open, about 200,000 hours were spent on the investigation at a cost of about $10 million USD. About 8,000 men were surveilled and about 650 were swabbed for DNA. In comparison, the FIGG investigation was much less intrusive, took about two months, and cost $217 for one DNA kit.

Unsolved cases leave substantial harm in their wake, and some of this comes from suspects who have difficulty clearing their name. For example, Joe Alslip was wrongly arrested and put on trial for the murders of Lyman and Charlene Smith in 1982, although the charges were eventually dropped for lack of evidence. Where cases are left open for long periods of time, many innocent persons are wrongly suspected, investigated, swabbed, and even sometimes wrongly arrested and convicted of crimes they did not commit. This has a corrosive and harmful effect on the community as a whole.

There were other notorious privacy intrusions in the investigation over the years as well, which you may find here. In Michelle McNamara’s I’ll be Gone in the Dark, Paul Haynes and Billy Jensen describe how they scraped data from public sites, including record aggregators, school yearbooks, local phone books, and genealogical records into a database of over 40,000 individuals (see pp. 294-7). Several prisoners had their DNA forcibly taken, and one set of human remains was exhumed. Investigations into serious crimes involve many privacy intrusions, and while these intrusions are authorized by the law it doesn’t mean that we can’t do better and use available technologies, like FIGG, to cast a much smaller net.

For those who like to view – or view again – the 2024 I4GG Conference, the video presentations will be uploaded to their website.

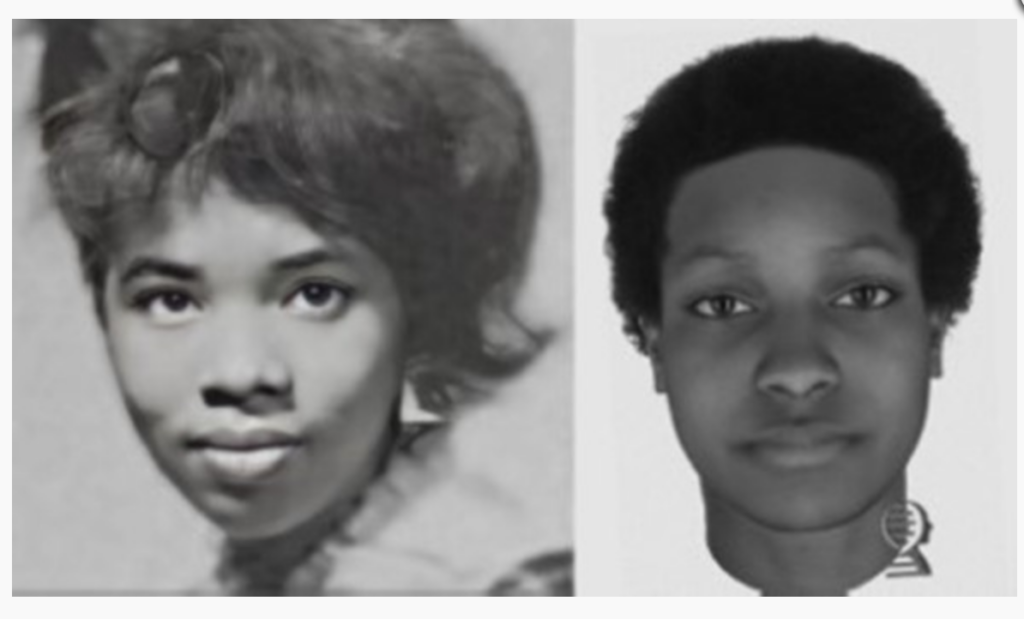

February Human Remains Case Solve: Sandra Young

Seventeen-year-old Sandra Young (Case ID 2189) was identified in February of 2024. Her skeletal remains were found on February 23, 1970, on Sauvie Island, Oregon. She was discovered buried in a shallow grave on the north end of the island by a Boy Scout troop leader, who noticed some items of clothing near the grave. An autopsy determined that she had suffered trauma, and was the victim of a homicide. A DNA profile was eventually developed and entered into CODIS, but there were no hits. Her information was also entered into NamUs. NCMEC also assisted in her case. A DNA profile suitable for genetic genealogy was developed from a fragment of her bone.

The Medical Examiner reported that, “Through a series of informative, poignant, and difficult interviews, Detective Helwig [of the Portland Police Bureau] learned that this individual not only lost a teenage sister when Sandra went missing in 1968 or 1969, they also lost a sister to gun violence in the 1970s. The family member was cooperative, supportive, and motivated to determine if the remains could be their sister, Sandra Young.”

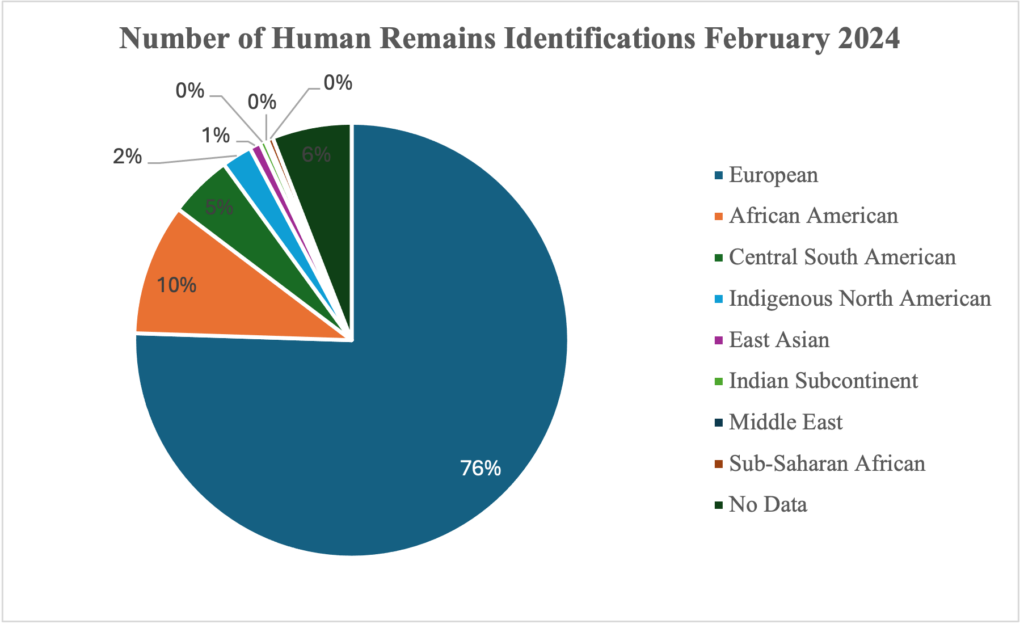

The identification of decedents like Young who are of non-European ancestry is more complex, because of the smaller number of DNA profiles in the databases and the distance of the relative matches. Here is data, updated as of February 2024, concerning the ancestry of decedents identified using FIGG:

| Bio-Geographical Ancestry | Number of Human Remains Identifications February 2024 |

| European | 370 |

| African American | 48 |

| Central South American | 23 |

| Indigenous North American | 11 |

| East Asian | 4 |

| Indian Subcontinent | 2 |

| Middle East | 1 |

| Sub-Saharan African | 2 |

| No Data | 29 |

| Total | 490 |

Of the non-European decedents identified, 9 out of 91, or about 10%, were reported as having a significant amount of European admixture. There may be other decedents who had European admixture as well, but where this was not reported.

Here is the same data visualized as a pie chart:

Young was born on June 25, 1951. She was a student at Grant High School in Portland when she went missing. Police continue to investigate her murder. Here is a picture of Parabon’s forensic phenotype of what Sandra Young may have looked like, alongside her high school yearbook photo, provided by the Oregon State Police.

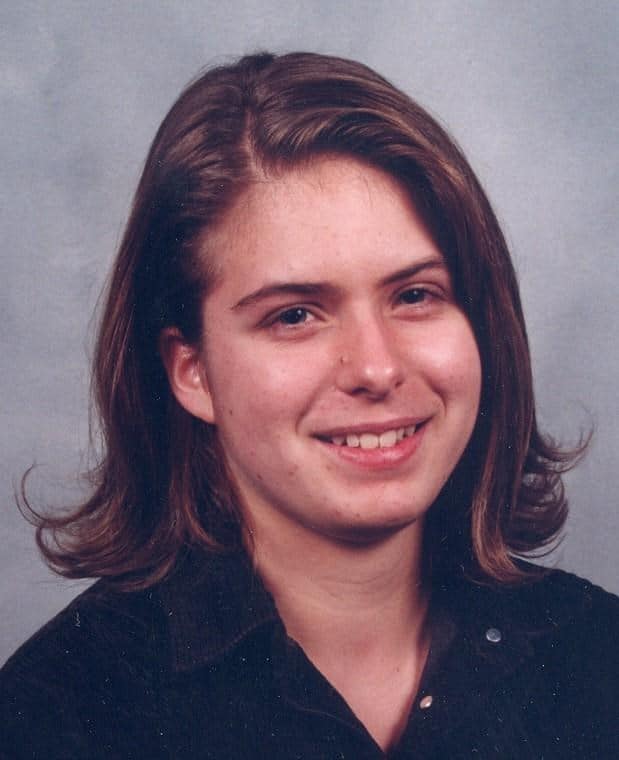

February Criminal Case Solve: Marc-André Grenon & Project Patronyme

One of the oddest cases yet solved – and one I currently know far too little about – is that of 47-year-old Marc-André Grenon (Case ID 2171). Grenon was arrested on October 12, 2022, and charged with the April 28, 2000 murder of 19-year-old Guylaine Potvin in Saguenay, Québec. Potvin was found deceased in her apartment in Jonquière, having been violently sexually assaulted. Information concerning the investigative techniques used was only revealed in February of 2024 when Grenon went on trial.

A DNA profile of a male suspect was developed from biological materials found on Potvin’s body, underneath her fingernails, on her belt, and on a box of condoms found at the scene. The DNA profile was uploaded to Canada’s National DNA Database, but there were no hits. The case eventually went cold.

Guylaine Potvin. Source: City News

The FIGG investigation was conducted by Québec’s public forensics laboratory, the Laboratoire de Science Judiciaires et de Médecine Légale, in partnership with a unit of the Sȗreté du Québec, formed specifically to tackle cold cases.

The DNA database used in this case is highly unusual – a forensic Y-STR database set up by the lab. Forensic biologist Valérie Clermont-Beaudoin testified at Grenon’s trial that the database, called project patronyme, was established in 2022. It analyzes STR profiles from Y chromosomes and suggests surnames that are associated with them. The database reportedly includes 138,000 DNA profiles that have been gathered from public genetic genealogical databases, from persons who “consent to the information being made public.” No further information is available right now on the composition of the database, or the manner in which consent was obtained.

Potvin testified that, “the software emits a list of potential last names that could be associated with the DNA, which are ranked by level of interest based on the degree to which they match.” The surname “Grenon” ranked first, with a score of 94 out of a possible 98 points. There is currently no information on the algorithms that drive the database search, or how results are ranked.

The database is reportedly only used when no other leads are available, and it provides a surname rather than an individual suspect. There are a few older cases that used the now-defunct Sorenson Y-STR database, but this is the first reported use of a forensic genetic genealogical Y-STR database being used for FIGG.

The final confirmation was made through surreptitious sampling. Police followed Grenon to a movie theatre, where one officer sat next to Grenon and his companion. The other officer retrieved the cup and straw from a garbage can where Grenon tossed it on his way out of the movie.

Grenon was tried in February 2024 on charges of first-degree murder and aggravated sexual assault in the Superior Court in Chicoutimi, Québec. He reportedly lived just behind Potvin’s apartment building at the time of the murder.

On February 20, 2024, the jury deliberated for only three hours before returning with a guilty verdict.

As with the Golden State Killer, police reported that DNA samples were taken from many suspects in the years while this case was open.

With the advent of forensic genetic genealogical tools like DNA Justice and projet patronyme, the days are numbered when we can say that GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA are the only games in town for FIGG. We can expect more tools designed specifically for FIGG to come on board in the future.

Thank you for reading!

Feel free to leave comments and information about case solves below. You may also access a copy of the FIGG Cleared Case Reporting Form here.